The Analytical Behaviors of Genshin Impact Lore Enthusiasts: An (Auto)ethnographic Look at r/Genshin_Lore

by Paul A. ThomasAbstract

This article is a digital (auto)ethnography that explores the analytical practices employed by members of the r/Genshin_Lore subreddit, focusing on how these individuals interact with, record and hypothesize about the lore of the video game Genshin Impact. The article begins by surveying how members of r/Genshin_Lore use a quasi-academic approach to the diegetic world of Genshin in order to "read" sources, share fan theories and debate those theories. The article then argues that the lore speculation on r/Genshin_Lore is a type of "narractivity" that balances canonical truth with creative conjecture. The article concludes by asserting that Genshin's fundamentally "drillable" storyline means that lore speculation can be productively seen as an "informational meta-game" within the game itself, and that r/Genshin_Lore's popularity can, in part, be attributed to the site serving as a convenient "place" for like-minded fans to congregate and play this meta-game.

Keywords: lore, fan speculation, drillable media, narractivity, autoethnography, fan theories

1. Introduction

Genshin Impact is a free-to-play fantasy video game developed by the Chinese company miHoYo and released in 2020. Drawing from real-world folklore, mythology and Gnosticism, the game follows the enigmatic "Traveler" as they explore the magical world of "Teyvat." Although the premise may seem simple at first glance, the game is distinguished from other games by its intricate "lore" (a term referring to a game's world-building, fictional backstory, or the history of its game-world; see Ford, 2021), which embues the narrative with a mysterious sense of depth. This dimension of Genshin has in turn spawned a dedicated community of "lore enthusiasts," who expend considerable energy sorting through the game's information sources, including in-game texts, character dialogue and visual motifs, to produce "fan theories" (de Amo & Garcia-Roca, 2021) about the nature of Genshin's narrative and its in-game history.

Members of the Genshin fandom flock to a variety of digital spaces to discuss the game's lore. In this article, I focus on the analytical behavior of those who participate on r/Genshin_Lore, a subreddit devoted to dissecting Genshin's mythos. Through digital and (auto)ethnographic methods, I explore how these individuals interact with, document and theorize about the game's lore. I argue that the fan theories on r/Genshin_Lore exemplify "narractivity" by blending speculative storytelling with the excavation of the game's future plotlines. Fan theorizing thus strikes a delicate balance between adhering to canon and engaging in creative speculation. Furthermore, I propose that Genshin's "drillable" storyline transforms lore speculation into an "informational meta-game" within the game itself. As a result, r/Genshin_Lore has become a vibrant space for those eager to play this analytic "meta-game," enabling the subreddit to attract an array of individuals who employ myriad methods to collectively piece together the game's intricate narrative puzzle.

2. Welcome to Teyvat

On September 28, 2020, the Chinese video game development company miHoYo released their latest game, an anime-inspired open-world fantasy RPG titled Genshin Impact (miHoYo, 2020). Although miHoYo had had previous success within the East Asian game market with games like Honkai Impact 3rd (2016), Genshin exceeded the company's expectations by becoming a worldwide hit (Adams, 2022; Dooley & Mozur, 2022; Lum, 2020). Five years later, the game is still going strong, with an average of around 57.3 million monthly users [1]. While the game is free-to-play, its optional gacha mechanics have, as of 2024, generated over $6.3 billion USD in mobile sales alone (Astle, 2024), helping miHoYo become one of the world's most-successful private video game companies (Royte, 2024).

Since its meteoric release, Genshin has sometimes found itself caricaturized as little more than a Zelda clone, set apart only by its array of digital waifus and husbandos. But such an understanding of the game is simplistic, overlooking an ambitious narrative that draws from Sino-Japanese aesthetics, world folklore, Christian Gnosticism and Abrahamic demonology. Genshin's main story focuses on the otherworldly "Traveler," who embarks on a quest across the magical world of "Teyvat" to find their lost twin. The Traveler serves as the game's initial player-character, [2] and it is through their interactions with the synthetic game-world that players are introduced to the unique properties of Teyvat itself. A key aspect of this world is that it is composed of seven primordial elements: "Anemo" (wind), "Geo" (rock), "Electro" (electricity), "Dendro" (plant life), "Pyro" (fire), "Hydro" (water) and "Cryo" (ice). Each element is typified by one of the seven "archons," [3] who in turn answer to a mysterious entity known as "Celestia." While much of the game focuses on exploration and combat, looming ever large in the background are questions about the archons, the (likely demiurgic) nature of Celestia, and the enigmatic origins of Teyvat (Jain, 2023; miHoYo, 2024).

Figure 1. The open world of Genshin Impact (miHoYo, 2020). Click image to enlarge.

To put it simply, the game's mythology -- being a complex tangle of fantasy tropes and esoterica -- is effectively a puzzle waiting to be solved. As a result, Genshin's lore (often drip-fed to players via in-game texts and easy-to-overlook lines of dialogue) has become a major draw for some players, many of whom dedicate considerable energy attempting to untangle the game's world-building. This article focuses on these “lore enthusiasts,” specifically those who flock to the r/Genshin_Lore subreddit to share their creative theories about the game's in-universe past or future, the nature of its characters and the "truth" of the game-world's diegetic cosmology (de Amo & Garcia-Roca, 2021, p. 3).

Although this is the first article to examine Reddit-based lore speculation vis-à-vis Genshin Impact, it is not the first to explore general "lore hunting" in gaming. Indeed, the recording and interpretation of game lore has been productively discussed with respect to Bloodborne (Ball, 2017; Schniz, 2016), Dark Souls (Ford, 2024; Jenkins, 2020), The Elder Scrolls (Jansen, 2018, 2021), League of Legends (Cantallops & Sicilia, 2016) and World of Warcraft (Krzywinska, 2008), among many others. When read in relation to one another, these studies largely share two key claims. First, video game lore is often created through a complex blend of environmental storytelling, ambiguous or fragmented narratives and unstable canon. Second, lore-analysis is participatory and archival in nature. With this article, I seek to further these claims, thereby providing additional evidence that lore-theorizing is a complex behavior that deserves greater scholarly attention.

3. Methodology

This project is rooted in the interpretivist approach to culture pioneered by Clifford Geertz (1973). It is fundamentally ethnographic and dedicated to documenting a unique human society. Like a traditional ethnographer, I have immersed myself in a particular culture I wish to study, participating in and observing its practices to gain an emic (insider) understanding of that culture's worldview (Brewer, 2000; Geertz, 1973, 1974; Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019; Spradley, 2016a, 2016b). However, unlike traditional ethnographies, which focus on people living in spatio-temporal "reality," this project studies cultural dynamics within an online space (Boellstorff et al., 2012; Hine, 2015; Jemielniak, 2014; Kozinets, 2020; Massanari, 2015). And as a digital ethnography focusing on video game fandom, this study owes much to the pioneering work of Boellstorff (2008), Kozinets & Kedzior (2009), Taylor (2009), Nardi (2010) and Pearce (2011).

Additionally, this work is autoethnographic in orientation. At its broadest, "autoethnography" refers to a post-modern research approach in which an investigator analyzes cultural phenomena while considering their own experiences (Adams et al., 2014; Ellis et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2013). Inspired by the work of communication theorist Carolyn Ellis (1997; 1999; 2004), contemporary autoethnographies tend to be evocative or poetic in nature. However, my use of "autoethnography" aligns more with Heider's (1975) original formulation of the term, referring to the ethnographic study of a culture in which one is embedded. In other words, this study is an "insider ethnography" in which I study a group to which I belong (akin to Jenkins, 1992; Hills, 2002; Jemielniak, 2014). To make this distinction, I have chosen to stylize my approach as "(auto)ethnographic" (à la Popova, 2020), given that this rendering foregrounds my decidedly ethnographic interests while also indexing my "insider" identity.

I employed three main methods in writing this autoethnography: memory work, online browsing and participant observation. The first method, memory work, follows Ellis et al.'s (2011) assertion that autoethnographic research is often done in hindsight and that usually, the researcher "does not live through [their] experiences solely to make them part of a published document" (p. 275). Such is the case here, as this study was not the result of a planned research intervention but rather a post facto analysis of my time in an online community that I have belonged to since 2022. In terms of specifics, memory work involved reflecting on and analyzing my personal experiences within the r/Genshin_Lore community that have shaped my understanding of the subculture (Monaco, 2010). I used Reddit's "History" feature to review my past interactions on the subreddit and reconstruct how those interactions unfolded.

The second method, online browsing (or "scouting"), is closely tied to memory work, as it involved the systematic reviewing of past discussions on r/Genshin_Lore. However, unlike memory work, browsing was a more general activity that focused on both discussions that I had participated in and those in which I had not. Furthermore, unlike memory work, which foregrounded my situatedness, browsing was used to map out the broader discursive themes of the community as a whole (Puri, 2007; Kozinets, 2020; cf. Geiger & Ribes, 2011). When browsing, I again used Reddit's "History" feature, along with the site's "Search" tools and the subreddit's unique system of bookmarks, flair and links, to find pertinent information.

Finally, I engaged in participant observation by posting threads, commenting on discussions and voting on submissions, all as a fan (Boellstorff et al., 2012, pp. 65-91). Initially, my participation was purely informal; after all, when I began contributing to the subreddit, I was involved solely as a fan, not as a researcher. However, in 2024, when I started to work on the paper that evolved into this article, my active memory work led me to realize that this previously informal and "fannish" behavior had arguably been a variant of participant observation that, through additional memory work, I could "excavate" for ethnographic material. Ultimately, this recontextualization was both strategic and performative, for in doing so, I sought to maintain my genuine perspective as an active insider while also forcing myself to critically reexamine, rather than passively accept, the dynamics in which I had long been embedded.

3.1 Fieldsite

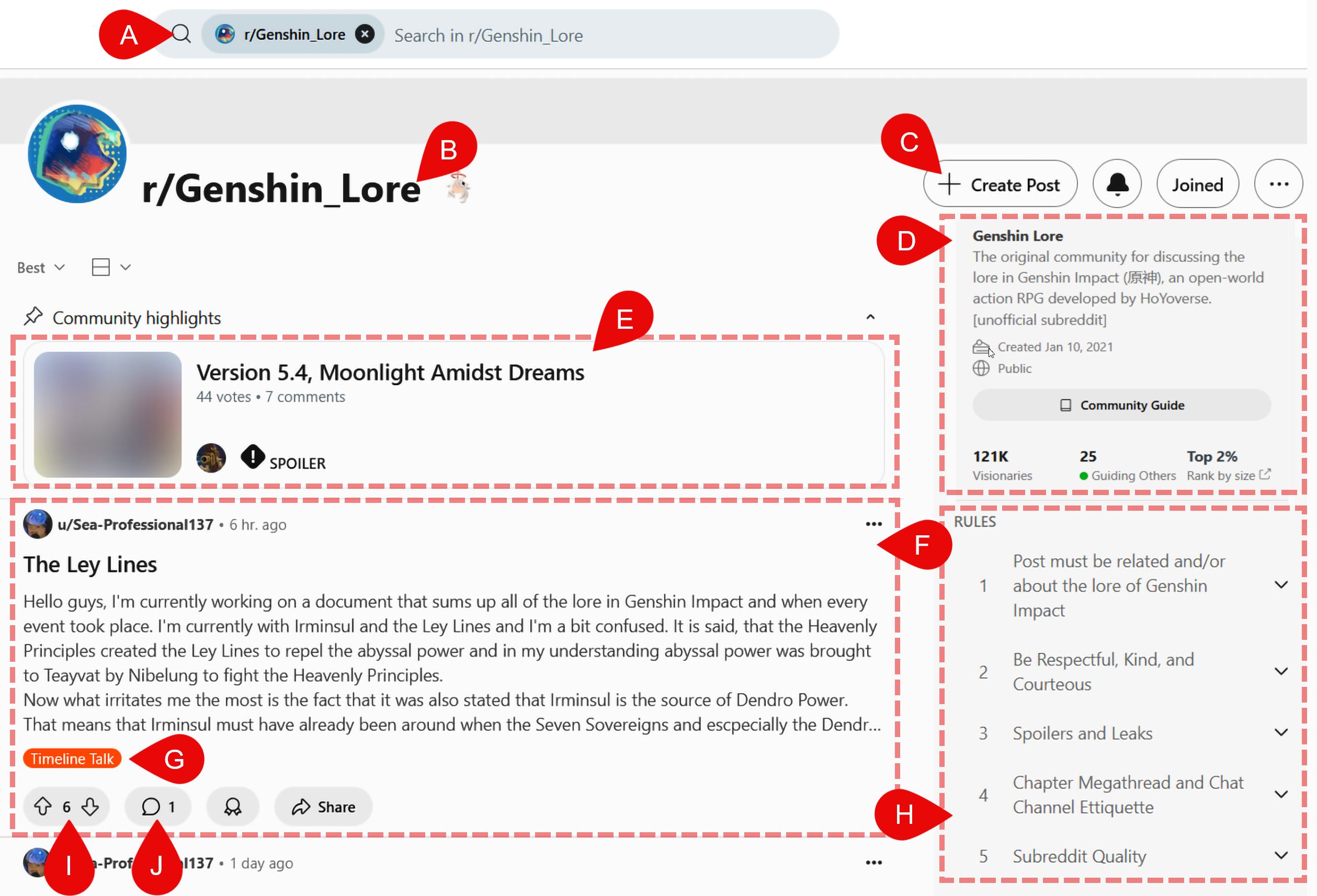

The focus of this article, r/Genshin_Lore (Fig. 2), is a subreddit on the popular social media platform Reddit (Anderson, 2015). Like its parent site, r/Genshin_Lore is an aggregative online space where members share "posts" (Fig. 2F) with one another. But unlike traditional forums, Reddit orders content based on its unique voting system, which allows members to "upvote" posts they find valuable and "downvote" those they think are unproductive, contentious, or off-topic. Posts and comments receive a "karma" score, which is the total number of upvotes minus any downvotes (Fig. 2I). High-karma posts appear near the top of the page, while low-karma posts are moved to the bottom. While karma scores are public, individual votes are anonymous and moderators also have the power to delete posts that violate subreddit rules (Massanari, 2015, pp. 2-4).

Figure 2. An annotated screenshot of r/Genshin_Lore, taken February 13, 2025. Click image to enlarge. A: The search bar. B: The top of the subreddit. C: The button to create a new post. D: A short summary of the subreddit's focus. E: An example "megathread." F: An example post. G: A post's "flair." H: The subreddit's rules. I: A post's "Karma" score. J: The number of comments made to a post.

At this point, it is worth noting that while the general behavior of Genshin lore enthusiasts is a topic of great scholarly potential, the members of r/Genshin_Lore are only a part of this community. Indeed, fans also discuss lore on Bilibili, Discord, TikTok, YouTube, HoyoLab and the Genshin Impact wiki, among many other sites. Furthermore, because posts made to r/Genshin_Lore are in English, the site does not represent the game's Chinese origins, its linguistically diverse player base, or its massive followings in non-Anglophone nations.

Regardless, r/Genshin_Lore is still a valuable site to consider, for several reasons. First, with over 120,000 subscribers, it is currently one of the largest hubs for English-speaking fans of Genshin to theorize about the game's lore. Second, a critical look at the site provides scholars with an understanding of how certain media fans engage with the narrative dimension of video games, both on an informational and an analytical level. Finally, its voting mechanisms and comment system provide an opportunity to explore how theories are created, discussed and refined through active online dialogue. While some research has explored the way online platforms both facilitate and shape narrative content (such as works that look at the SCP Foundation Wiki; see Ferguson, 2022; Jones, 2022; McCullough, 2022), relatively little research has focused on Reddit, despite the site's unique framework that enables participatory and collaborative storytelling (Elstermann, 2023).

4. Results

4.1 An Academic Approach to Fictional Lore

A key assertion of this study, echoing a claim made by Jansen (2021), is that members of the r/Genshin_Lore subreddit tend to approach lore speculation in an "academic" way. Often this is done by engaging in a sort of "fictional historiography," wherein a theorist uses historical methodology to explore the synthetic past of a fictional world (Westman, 2022, pp. 57-61). In doing so, lore enthusiasts will emulate "the stylistic and narrative conventions of twentieth- and twenty-first-century historiography" by meticulously collecting, reading, citing and critiquing (often diegetic) sources to further their speculations about the game's lore (p. 59) [4]. Of course, the techniques of historians are not the only ones employed by lore enthusiasts: other fans will conduct archaeological surveys of the game's ruins (a variant of "archaeogaming," see Reinhard, 2018; 2019), [5] linguistically analyze the game's languages (arguably an example of "ficto-linguistics," Ferguson, 1998), [6] or cartographically document the fictional geography of Teyvat (akin to Fonstad, 2006) [7] to generate theories.

Lore enthusiasts sometimes embrace this academic approach in a satirical way, [8] but more often than not, it is employed earnestly to excavate the "truth" of the game-world. This observation corroborates Hill's (2002) claim that fan-scholars often draw on "academic knowledge" -- in this case "legitimate" research methodologies -- "in order to express their [genuine] love for a text" (p. xxxi). In many ways, the unique blend of rigorous analysis and playful speculation found in r/Genshin_Lore can be compared to the Sherlock Holmes fandom's "Grand Game," wherein fans treat Doyle's novels as historical documents to-be-studied (Polasek, 2014). Like the participants in the "Grand Game," the members of r/Genshin_Lore engage in "serious play," or behavior wherein individuals "voluntarily devote enormous amounts of time, energy and commitment [to a task] and at the same time derive great pleasure from [the] experience" (Rieber et al., 1998, pp. 29-30). This results in a unique fusion of academic rigor ("serious") and fannishness ("play").

4.2 Internal and External Sources of Lore

The theories crafted by members of r/Genshin_Lore draw upon two types of informational sources: those that are "internal" and those that are "external."

"Internal sources" can be defined as any in-game text -- broadly understood as any "discursive structure of potential meanings" (Fiske, 1989, p. 27) -- that communicate information about the story-world. Such sources can be broadly sorted into two main categories: "flavor text" and "diegetic indexicals." The former refers to text that has little function other than providing the player with background information about a game-world (van Stegeren, 2022, pp. 5-7; Tremblay, 2023, pp. 36-38). In Genshin Impact, this includes character bios, item and location descriptions, quest summaries, loading screen "tips" and "ruby annotations" (see Sandro, 2020, p. 36) used to gloss certain words of dialogue. Though technically existing within the game, flavor text strictly operates outside the context of the game's story by providing information about the game not to the player-character, but to the human player who exists outside the game-world context.

Diegetic indexicals, on the other hand, are internal sources that reflect the spatio-temporal limits of the game world. They communicate the restricted awareness of the game’s characters, and the socio-cultural power dynamics that would have produced the game-texts in the first place. Diegetic sources include lines of dialogue delivered by the game's various fictional characters, in-game texts (that is, diegetic sign-objects like in-game books, letters, posters and inscriptions) and environmental details (like architectural styles, flora/fauna, or character designs) that non-verbally that "point" to or reference some deeper truth about the history of the game-world (cf. Jenkins, 2004).

A unique aspect of diegetic indexicals is that, by their very nature, they are often full of purposeful bias, elision, ellipses and lacunae (cf., Andriano, 2024). In other words, they exemplify what Eco (1989) calls "open works," whose "gaps" engender a "plurality of interpretations," (p. 8) in this case about the truth of Teyvat's past. The task of the theorist is to analyze these open works in relation to their "field of relations" (for example, the context of the dialogue or indexical, the known canon of the game as it pertains to the source under scrutiny, or previously discussed fan theories) and to generate evidence-based theories that seek to reflect "the world intended by the author" (p. 19; cf. Van de Mosselae & Gualeni, 2023).

Figure 3. A screenshot of a diegetic indexical -- in this case, a mural found in the desert ruins of Sumeru -- that uses art, inscription and environmental details to inform the player's understanding of the game-world's backstory (miHoYo, 2020). Click image to enlarge.

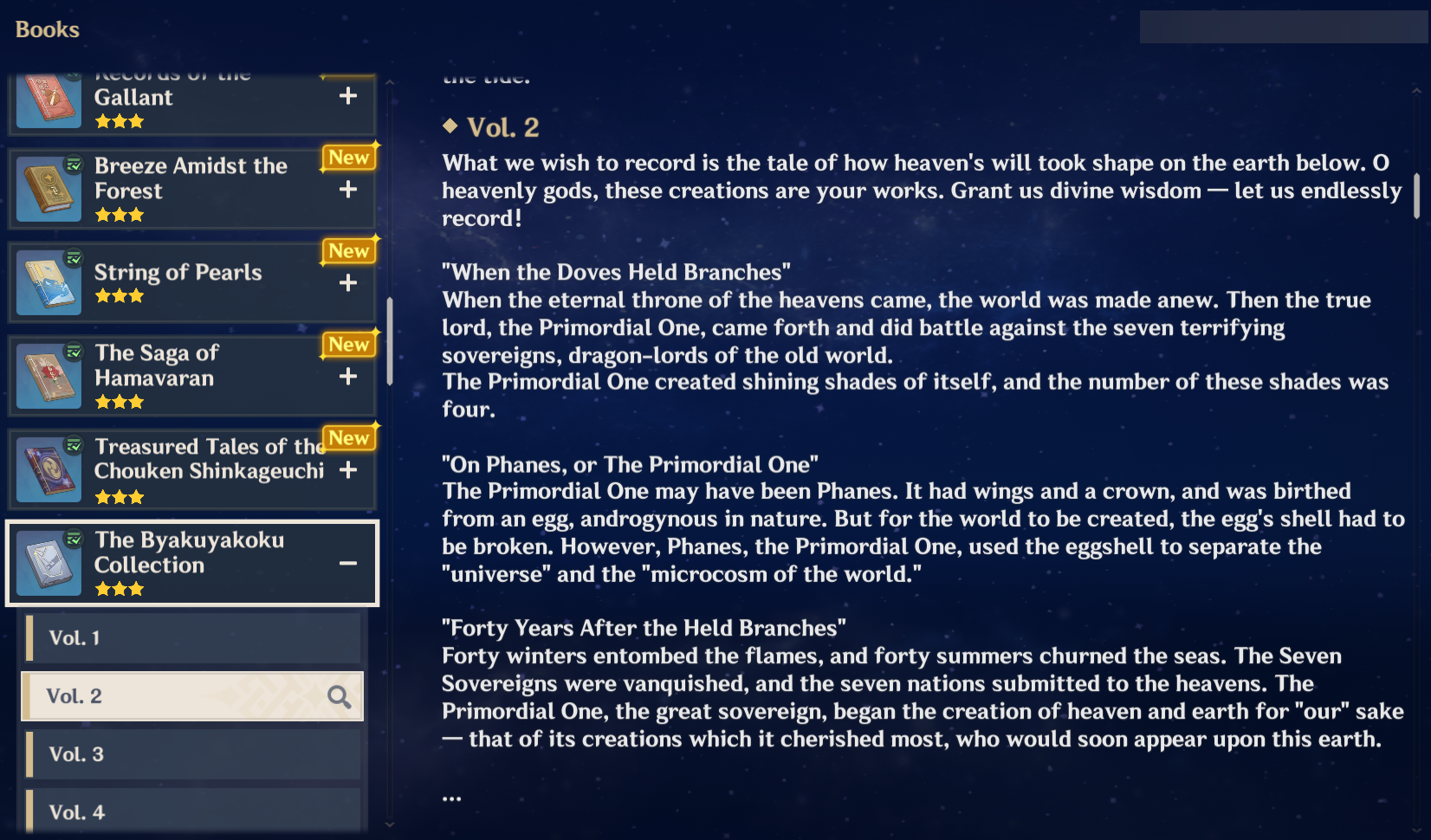

Among the various diegetic indexicals, perhaps the most crucial for lore enthusiasts are books: short, digital works of expository text providing background information about the game-world (cf. Jansen, 2018). As of February 2025, over 280 books or book volumes can be found scattered across Genshin's diegetic game-world, and whenever a new text is added to the game, members of r/Genshin_Lore carefully examine it, aware as they are of the game's tendency to use these indexicals to reveal important story developments. A prime example is Before Sun and Moon, a short book that players can discover in the "Enkanomiya" region after completing the "Collection of Dragons and Snakes" quest (Fig. 4). Though seemingly insignificant at first glance, this work actually contains the truth about Teyvat's origins: Eons before the game's events, the world was controlled not by Celestia but by elemental dragons. These beings were then defeated by the "Primordial One," who transformed the dragons' world into Teyvat, making it suitable for its own creations: humanity.

Figure 4. The text of Before Sun and Moon, as recorded by in-game archive (miHoYo, 2020). Click image to enlarge.

In-game dialogue further reveals that Before Sun and Moon is anathema to Celestia, who has suppressed the text for its heretical revelation that it is not an all-powerful creator deity, but rather an alien usurper from a mysterious "beyond." Needless to say, this book's release transformed players' understanding of the game-world. Suddenly, an idyllic past-that-never-really-was ("Celestia as the eternal Godhead") was replaced by an almost Lovecraftian past-that-was-never-meant-to-be-known ("Celestia as the demiurge"). Before Sun and Moon can thus be viewed as something like the Genshin fandom's New Testament, which revised and recontextualized mythological information about the diegetic past, providing a new, ostensibly "correct" starting point for future discussions of narrative truth. In this way, the book revealed to many lore theorists the discursive nature of in-game history, or the ways that "Canon" is always a created object and statements from otherwise "authoritative sources" cannot simply be accepted at face value (cf. Jansen, 2021).

In addition to internal sources, many lore enthusiasts employ external (that is, non-diegetic) sources to craft their theories. These sources tend to be non-fictional works that focus on the religious, mythological, linguistic, or socio-cultural concepts that theorists believe the game is referencing. Popular external sources include the Ars Goetia (a mid-17th century grimoire containing an outline of seventy-two demons whose names are referenced in the game), [9] Gnostic works from the Nag Hammadi library (for example, the "Hymn of the Pearl," a passage from the apocryphal Acts of Thomas alluded to by the game), [10] the psychological work of Carl Jung (whose concepts fans often use to analyze the game's symbolism), [11] and the theosophical writings of Helena Blavatsky (whose Theosophic concepts are referenced throughout the "Narzissenkreuz" story quest) [12].

External sources focusing on philosophy [13], psychology [14], world languages [15] and popular culture [16] are also popular. Similarly, theorists will often cite lore-focused videos released by popular Genshin YouTubers (for example, Ashikai, Chill with Aster, Teyvat Historia, MurderofBirds, CatWithBlueHat, Roozevelt, Minsleif and Wei), or the meticulously cited Genshin Impact wiki, using the perceived credibility, authority, or comprehensiveness of these sources to strengthen specific claims (cf. Thomas, 2018, pp. 294-296; Jenkins, 2020, p. 136).

4.3 "Reading" Sources

The next topic to consider is how members of the r/Genshin_Lore subreddit read their sources (that is, how they "identify and decode a certain number of signs, [and how they] put them into a creative relation between themselves and with other signs"; Paolo Terni in Hall, 1980, p. 124). Broadly speaking, lore enthusiasts approach this process from what I will call either a "formalist" or "hermeneutic" perspective.

The formalist perspective, reminiscent of the analytical tendencies found in "New Criticism," treats the game as a self-contained "unit of meaning" (Augustyn, 2011, p. 225; see also Zygutis, 2021). The formalist approach is "intensive" (Tulloch & Alvarado, 1983, p. 2), with its proponents focusing on the referential (diegetic) and explicit (purposeful) truth of the game's lore (Bordwell, 1989, p. 8). Put simply, formalists analyze the game at face value, excavating it for information about its story-world and interpreting that information from within that world's boundaries. For an example of this approach, consider the following critique made by a Redditor about a post entitled "Genshin, Jacques Lacan, and Gnosticism," which attempted to read the game through a psychoanalytic lens. In their critique, the Redditor argued that this reading is:

… entirely unnecessary to explain what's happening. Celestia, the heavenly gods, is trying to keep Teyvat in the state that allows them to rule over it. The archons led by the Tsaritsa, the chthonic gods, don't like Celestia's yoke, and want to reshape the world according to their vision. The humans want to get rid of all gods entirely and take the world for themselves. The Abyss Order seeks to make Teyvat their Lebensraum and have their revenge. [17]

This user's reading of Genshin focuses on what the plot is literally saying. They are not speculating about potential inspiration, nor are they searching for hidden metaphors. Instead, they are focusing on the "intended and conscious" meaning of the game. However, such a straight-forward approach is problematized by the fact that lore-enthusiasts tend to prioritize different in-game sources when attempting to reconstruct "literal" in-game events. Further complicating matters is how the game itself underscores that even "authoritative" sources can be misleading or just plain wrong (cf., Jansen, 2018, 2021). How are players to find the "intended and conscious" meaning of the game if they cannot even take its sources at face value?

This is where the hermeneutic approach comes into play. Proponents of this approach do not confine themselves to the diegetic "reality" of the game. Instead, they frequently seek out "real-world" sources, which they use to inform -- and, in some cases, guide -- unique readings of the game. The hermeneutic approach is thus an interpretative enterprise (Bordwell, 1989, p. 9), in which the theorist looks for the implicit (symbolic) and/or symptomatic (repressed) meaning of lore (pp. 8-9). Emblematic of the hermeneutic approach is the post "Furina is Jesus," written by Pear_Necessities. In this short essay, posted to the subreddit before the conclusion of the Fontaine "archon quest," the author argues that, because the quest seemed to purposefully allude to Judeo-Christian concepts like the Great Flood and "original sin," by the end, "Focalors will die for Fontaine's sins and absolve her people [and] Furina… will then ascend and gain a vision" [18]. The important thing here is not that the theory ended up being largely correct, but that Pear_Necessities produced their theory by "translating" the game's meaning through some external lens (in this case, Christian theology).

But the hermeneutic approach to lore is not without its shortcomings, with the biggest issues being the risk of apophenia (wherein a theorist postulates a supposed connection between unrelated game elements) or over-interpretation (wherein a theorist projects their own beliefs, biases, or knowledge onto the game, resulting in a reading that is logically tenuous or unnecessarily complex). To prevent these issues, hermeneutic theorists often go to great lengths to explain why the game should be interpreted through a specific external text, if at all.

At this point, I must emphasize that the "formalist" and "hermeneutic" perspectives are not mutually exclusive categories: some lore enthusiasts use only one approach when reading sources, whereas others use whatever approach they feel is contextually appropriate. For this reason, it is best to understand these approaches, to borrow the phrasing of Mittell (2015), as "vectors or tendencies… with fluidity and blur between" them (p. 315).

4.4 Sharing and Searching for Theories

After gathering and reading sources, lore enthusiasts will compile the information they have gleaned into a coherent "theory," which they will then post to the subreddit for other fans to read. Theories tend to be shared as one of the following:

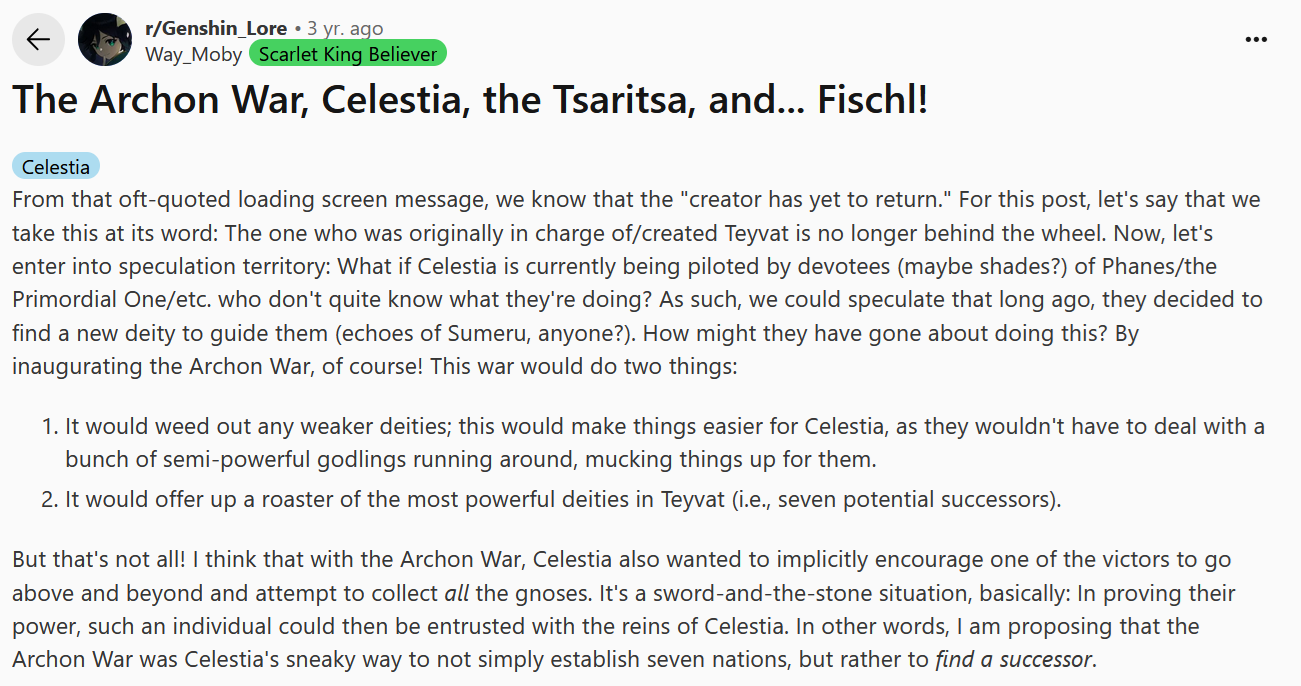

- Essays: Most lore enthusiasts share their theories as text-based "essays" (Fig. 5). These write-ups propose an argument about the game's story. In line with academic practices, essays tend to feature intertextual markers (such as footnotes, hyperlinks and parenthetical citations) to source information (de Amo & Garcia-Roca, 2021, p. 3). Arguably, the comments that members of the subreddit leave on submissions can be understood as essays, too -- albeit ones that exist on a smaller, more succinct scale.

Figure 5. An example essay posted to r/Genshin_Lore. Click image to enlarge.

- Videos: Some theorists share theories via video presentations. Among these productions, "video essays" are the most popular. Like text-based essays, these videos detail, discuss, or speculate about the game's lore, but unlike text-based essays, video essays tend to incorporate dynamic footage. This helps to visually bolster a theorist's argument while keeping viewers engaged. And of course, not all videos are essays: One unique work, created by Turkeyball123, is a detailed time-lapse video tracking the shifting battle lines in the war between the Inazuma Shogunate and Watatsumi Island [19].

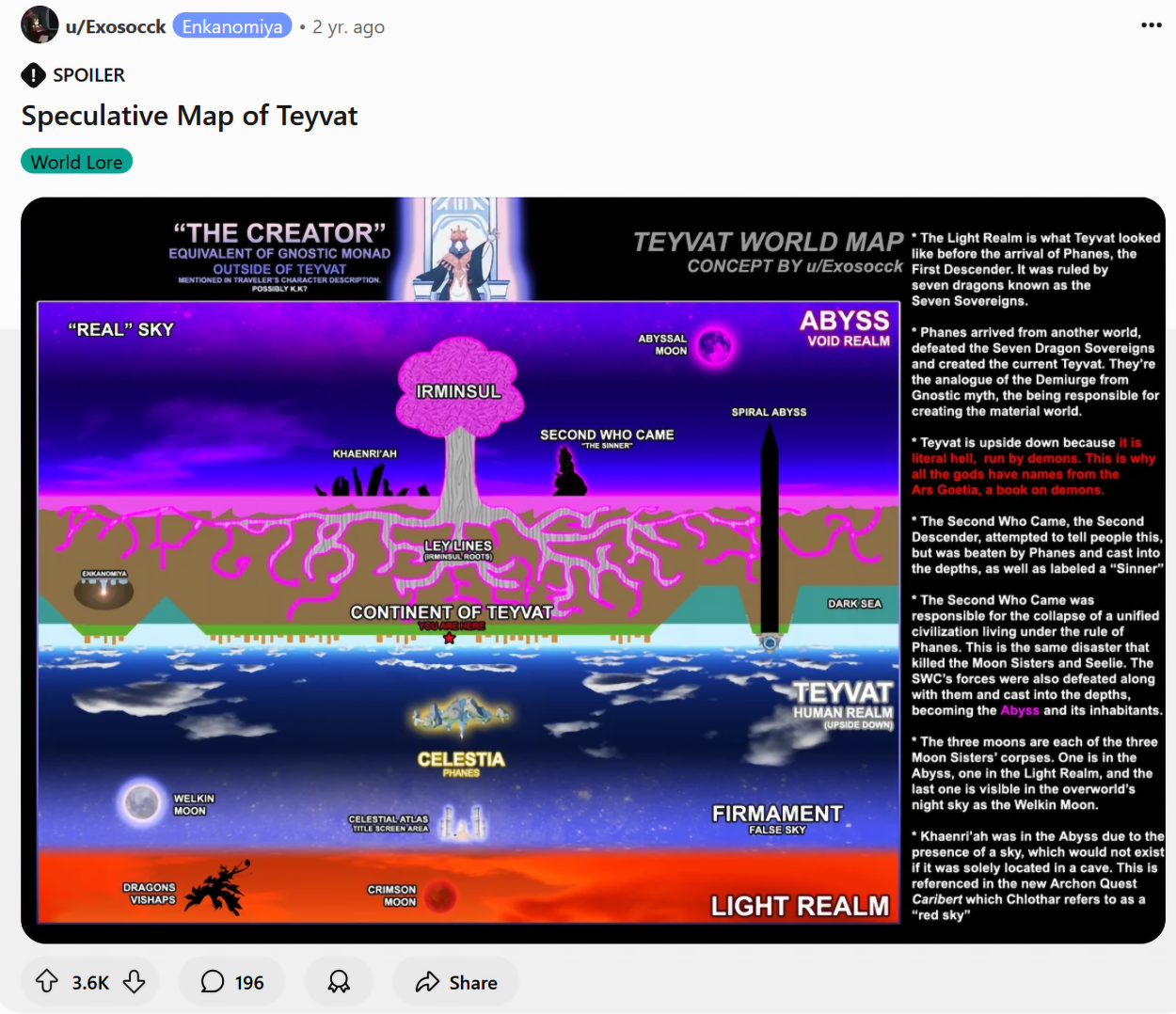

- Images: Other lore enthusiasts convey theories through still images, ranging from simple charts to intricate diagrams. Images can enhance the presentation of a theory or discussion, and they are regularly used in conjunction with written essays or videos (Fig. 6). Thanks to the format's high "spreadability" (Green & Jenkins, 2011), images have proven to be among the subreddit’s most popular posts. On weekends, members of the r/Genshin_Lore sub are allowed to post humorous lore-related "memes," which are often image-based. Although not as analytical as serious posts, these memes serve an important meta-discursive purpose, allowing subreddit members to comment on or critique popular topics of discussion via parody, satire, sarcasm and irony [20].

Figure 6. An example of an image that shares a visual theory -- in this case, about the cosmology of Teyvat. Click image to enlarge.

To prevent frivolous or off-topic submissions, the r/Genshin_Lore moderators regularly post "Chapter megathreads" [Fig. 2E], in which subreddit members can discuss the game in a less formal, more ad hoc way. Content normally prohibited in main posts, such as random questions about lore, is usually allowed in these megathreads.

After a theory is posted, it is vetted by a moderator before appearing on the r/Genshin_Lore homepage. Visibility on the main page is based on a post's age and popularity: newer submissions that are well received will stay "up" longer, whereas older, less popular submissions will recede into the digital background. To locate older posts, visitors to r/Genshin_Lore can use Reddit's standard search engine (Fig. 2A), or they can utilize the subreddit's distinctive "flair system" to simplify the process (Fig. 2G). This schema, which functions similarly to a sophisticated tagging system, ensures that whenever a post is submitted, it is paired with a unique marker (known as "flair") identifying the focus of that post. Visitors can view specific topic posts in r/Genshin_Lore by clicking the flair marker on the right side of the screen. This will hide all posts not tagged with the chosen flair marker.

4.5 Discussing and Critiquing Theories

When a theory post goes live, other members of the subreddit are allowed to comment on it. During these discussions, members applaud or dissect theory, reviewing its strengths, weaknesses and underlying assumptions. While these debates are not inherently antagonistic, they often do involve critique. Criticism typically centers on one of the following aspects:

- Effort: Theory posts are expected to meet a quality standard, which members of the subreddit often deduce based on the perceived effort that went into a post's creation. "High effort" posts tend to be seen as those featuring certain elements (like sources, thematic organization, or references to other theories) that suggest a poster has invested time and energy into the formulation of a theory. In contrast, "low effort" posts -- such as lazy "shit posts" or those that "state the obvious" -- are verboten. To prevent their theories from being brushed off as "shit posts," some theorists will proactively categorize their contributions as "crack" ("Crack," 2023), implying that while they might initially seem "cheap" or insincere, they have been posted in a good-faith attempt to generate productive -- albeit, often humorous -- discussion [21].

- Level of Analysis: "Analysis" can perhaps best be glossed as "informed speculation," typically accompanied by a central thesis that makes some reasoned statement about the story-world. Depth of analysis can be determined by considering a theory's sourcing, the strength of its logical structure and its originality. Note that some content shared on r/Genshin_Lore focuses less on analysis proper and more on synthesizing the game's canonical storyline -- an approach similar to the behavior of Fandom.com contributors (Magpantay, 2022). While information synthesis might appear to be nothing more than mere regurgitation, it is a process that still requires creative thinking, personal judgment and the strategic use of citation, making it a form of analysis in its own right.

- Evidence: Theories tend to be ill-received if the poster fails to provide internal and/or external evidence to support a claim (cf. de Amo & Garcia-Roca, 2021, p. 3). Theories lacking evidence (which de Amo and Garcia-Roca [2021] dub "alternative theories," pp. 5-6) or those that reject whole swaths of the game's canon are often written-off simply as "wrong." On r/Genshin_Lore, common criticisms include the charges that a theorist has "misread" evidence (with "misreading" referring here to both legitimate misunderstandings of game text as well as those oppositional readings of key evidence that a given poster might not agree with; see Hall, 1980, p. 127), mistranslated key texts (often in relation to the game's Mandarin version or its English localization) or used "irrelevant" sourcing [22].

When theorists who "read" information in contrasting ways encounter one another, it is not uncommon for debates to arise. In instances like this, the debates tend to be metapragmatic (that is, "meta-discursive" or "meta-indexical," see Silverstein, 2022, pp. 20, 43), focusing less on the game's lore and more on the "proper" way to read that lore. Such debates are thus ideological in nature, and they often force participants to acknowledge, reflect on, defend, or abandon their normally unanalyzed approaches to theorizing (cf., Overstreet, 2015, pp. 1-2).

Reddit's upvote/downvote system serves as an additional structure for critique, ostensibly separating the "good" theories from the "bad." However, some members of r/Genshin_Lore downvote content simply because they disagree with it, regardless of its productivity. This can lead to groupthink and echo chambers, in which content is upvoted merely for conforming to the majority's beliefs (Gouvea et al., 2019; Lim et al., 2017; Morini et al., 2021). In contrast to the voting system's "wisdom of the crowds" approach, the moderators of r/Genshin_Lore have also created a series of awards for theorists who they believe have excelled in translation (the "Handy Handbook of Hilichurlian" prize), made groundbreaking contributions (the "Pir Kavikavus Prize"), or whose speculative theories have proven correct (the "Crown of Insight"). These awards function as positive critique mechanisms, that function in a more personal, discerning manner. These awards, like Reddit's voting system, serve as a critique mechanism, but they also provide feedback that is positive, personal and more carefully curated.

5. Discussion

5.1 r/Genshin_Lore and Speculative Narractivity

Having elucidated the behavior of r/Genshin_Lore's contributors, I now wish to delve into the nature of "theory posts," specifically by considering the type of fan text they exemplify. To answer this question, I want to begin by considering the work of Jason Mittell (2015), who argues that media texts often approach storytelling from either a "What is" or "What if?" perspective. The former, Mittell contends, include texts that attempt "to extend the fiction canonically, explaining the universe with coordinated precision and hopefully expanding viewers' understanding and appreciation of the story-world," whereas the latter include texts that pose "hypothetical possibilities… alternative stories and approaches to storytelling that are distinctly not to be treated as potential canon" (pp. 314-215). Mittell (2015) further contends that "What is" texts tend to be interested in "proper solutions and final revelations," whereas "What if?" texts generally focus on the pleasure of conjecture (pp. 315-316).

While Mittell's argument was initially made with respect to transmedia texts, he notes that his ideas can be imported into a discussion of fan works by thinking of "'What is' fantexts" as those that document the "truth" of a media world (such as fan concordances focused on documenting the "canon" of a media object) and "'What if?' fantexts" as those that non-canonically expand on a fictional universe (like fan fiction). How then do the theories on r/Genshin_Lore fit into this "What is"/"What if?" framework? The answer is somewhat complicated. While these works excavate the game's plot while attempting to stay faithful to its "truth" (like "What is" texts), they also generate speculative ideas about canon (like "What if?" texts). Theory posts thus come to occupy the fluid area between the two approaches (Mittell, 2015, p. 315), and this blurring, I argue, is due to their inherently "narractive" nature.

First defined by Paul Booth (2009), "narractivity" is a unique semiotic process "by which communal interactive action constructs and develops a coherent narrative database" (p. 373). Booth argues that when fans piece together the story of their media object of interest, they are not merely regurgitating facts, but actively remixing those facts to produce a complex web of potentiality. "By… re-reading [a] story" in this way, Booth contends that "fans create a new discourse… connecting kernels and satellites of the plot into a [new] narrative structure" (p. 388). Booth maintains that fan wikis and media spoilers exemplify this behavior, given that the former allow fans to (re)construct a media object's canonical narrative (p. 380) and the latter enable the inscription of speculative theories and thus "assert the truth of the may be" (p. 385). r/Genshin_Lore enables both as well: in many instances, users (re)construct the game's narrative by compiling and (re)reading its canon, and in other instances, they explore the game's ambiguities to hypothesize about the game's history or future. This process generates speculative theories that subreddit members can ultimately accept, reject, or expand upon.

One interesting aspect of this speculative narractivity is that it can lead lore enthusiasts to internalize theories as canonical "fact," especially when these theories are repeated by others. For example: one text in Genshin explains that King Deshret (an ancient deity who ruled over a desert nation eons ago) "reject[ed] the gift granted by the divine throne." Given what is known of Deshret's motivations, many fans have reasonably interpreted this line to mean that Celestia once offered to make Deshret an "archon," but he refused the offer. The text, however, does not literally say this; the idea that "gift" is synonymous with "archonship" is a reasonable but ultimately speculative "headcanon." Nevertheless, this interpretation has been so widely circulated that now, when discussing Deshret's story, many members of the subreddit -- myself included -- tend to implicitly accept it as narrative fact. But by taking an interpretation and automatically elevating it as canon, members of the subreddit are "assert[ing] the truth of the may be" (Booth, 2009, p. 385), thereby eliding the "What is" with the "What if?" (cf. Ford, 2024)."

5.2 The Allure of Lore and r/Genshin_Lore: An (Auto)ethnographic Consideration

Now that I have explored the "What?" and "How?" of r/Genshin_Lore and its lore enthusiasts, I wish to tackle the question of "Why?" Why might fans speculate about Genshin's lore, and why might they congregate on r/Genshin_Lore? Answering these questions is, of course, easier said than done; in the end, each person who contributes to the subreddit has their own reasons for doing so. That said, it seems uncontroversial to say that many players formulate and share theories because it provides them with a sort of surplus pleasure. Simply put: it is fun! But what exactly is the nature of this pleasure, and how does it relate to the existence of the r/Genshin_Lore subreddit? To answer these subjective and affectively charged questions, this section will employ a more autoethnographic approach by exploring the reasons why I myself enjoy theorizing about lore on r/Genshin_Lore. After first outlining my own thoughts, I will then explore them in relation to pertinent literature.

Let me start by saying: It was the lore of Genshin that drew me into the game. It was the lore of Genshin that convinced me to give it a try. When first introduced to Genshin in 2021, I, like many others, assumed that it was just an anime-inspired Zelda clone. But then, after watching my wife play through several quests, I started to notice the game's detailed interest in the history of its story-world. Ever since I was introduced to the Lord of the Rings as a child, I have been captivated by fictional mythologies in media. Needless to say, Genshin's rather complicated lore ignited my curiosity, and I decided to give the game a chance.

After creating my account in early 2022, I threw myself into the game, eager to learn all its secrets. Regardless of whether I was in the darkest of dungeons or on the steepest of cliffs, I was always on the lookout for hidden information that could tell me more about Teyvat's mysteries.

I wanted to overturn every strange rock…

I wanted to explore every ruin…

I wanted to read through every newly unearthed text…

On one level, digging into these little details about the game's rich and expansive lore was appealing because it helped me to better appreciate the game's story and its characters. But on a deeper level, this sort of "semiotic excavation" was appealing because it encouraged me to find information and form unique interpretations about the digital world around me.

For some readers, my use of words like "excavate," "dig," and "unearth" in the preceding paragraph may recall Jason Mittell's (2015) concept of "drillable media": media objects that encourage "fans to dig deeper, probing beneath the surface to understand the complexity of a story and its telling" (p. 288).These sorts of works tend to have rich world-building, which leads fans to dive into that world, latch onto the elements that resonate with them and then speculate about their meaning. In doing so, fans -- who often comprise a "forensic fandom" (Mittell, 2015, p. 52; 2020) -- are encouraged to chip through a media object's many layers of meaning to uncover some deeper narrative "truth" that is not obvious at first glance. This provides fans with the chance to "connect the narrative dots" (Mittell, 2015, p. 289) and "solve" some underlying mystery. Drillable media consequently have a ludic quality to them; these objects act as a kind of game, with their "truth" functioning as a prize that fans can (at least, in theory) "reach" via constructive theorizing (cf. Ball, 2017). This is exactly the case with Genshin Impact.

It is worth noting that in his discussion of drillable media, Mittell largely focuses on long-form television productions, like Lost, The Sopranos, The Wire, 24 and Battlestar Galactica (Mittell, 2015; 2020). Although these productions have ludic elements, they are not conventional games, strictly speaking. Genshin Impact, on the other hand, is. People play it by clearing objectives, battling monsters, completing quests, finding treasure, unlocking way points, progressing through ongoing story updates, etc. However, exploring lore -- speculating about the cosmology of Teyvat or theorizing about a character's upbringing -- does not help a player beat a boss or earn in-game rewards. This means that speculating about lore provides a sort of surplus pleasure only experienced by players who look outside the game's normative victory parameters. Of course, this has led some to write off lore as a "narrative wrapper," a nebulous layer of "extra information unrelated to gameplay" Bembeneck, 2015, p. 43). And yet, despite its supposed superfluousness, people, myself included, still "play" with this wrapper.

For this reason, I propose that Genshin lore speculation can be viewed as an "informational meta-game" that exists within -- or perhaps "behind" -- the framework of the traditional gaming experience (cf. to Schniz's [2016] concept of "cryptic ludonarrative"). When viewed from this angle, theorizing about lore can be understood as a meta-ludic activity providing "extra intrigue for the interested player" (Ford, 2021, "Digital Materiality," para. 9) outside the boundaries of "regular" gameplay. Put another way, lore theorizing effectively functions as its own game that allows fans to creatively experience a sense of achievement and mastery over the game's narrative. This, in turn, provides the theorists with the satisfaction of "winning" at an aspect of the game that is not conventionally seen as "winnable."

But once again, how does this help explain r/Genshin_Lore's popularity? Simply put, the subreddit -- as an accessible hub for lore enthusiasts to exchange ideas, theories and conjectures -- functions as a digital "community of practice" (Hills, 2015) for those interested in Genshin's informational meta-game. For many, the promise of a like-minded community is compelling. Speaking once again from personal experience, while I have friends who play Genshin, none share my deep interest in its lore. Prior to discovering r/Genshin_Lore, I tended to keep my theorizing to myself, lest I annoy my friends with a topic they cared little about. Not only was this self-muzzling a tiring activity, it was also lonely. I felt as if no one understood my love for the depth of the game's story-world. But then one day I stumbled upon r/Genshin_Lore and found myself surrounded by fans who loved that depth, too. I finally had a space where I did not feel so isolated. And though my experience is anecdotal, it aligns with studies that suggest it is the promise of community that often draws individuals to fan spaces (Larsen & Zubernis, 2011; Parsakia & Jafari, 2023; Reysen et al., 2017; Reysen et al., 2022).

6. Conclusion

In this article, I have attempted to document the way that members of r/Genshin_Lore analyze and theorize about Genshin Impact's lore. I argue that lore enthusiasts tend to employ practices found in academia to gather, analyze and critique both in-game and external sources and that they often approach their investigations from either a "formalist" perspective (which prioritizes internal consistency), or a "hermeneutic" perspective (which delves into symbolic and symptomatic meanings often drawn from real-world sources). The sharing of theories on r/Genshin_Lore takes various forms, with some enthusiasts disseminating their ideas as essays, videos, or images, but regardless of format, most submissions strive for fannish rigor via evidence-based arguments. Theories posted to r/Genshin_Lore are often critiqued or discussed by the subreddit's participants, with discussions usually centering on the quality of a post, its depth of analysis and the nature of the evidence provided.

As fanworks, theory posts submitted to r/Genshin_Lore blur the line between "What is" and "What if?" texts, engaging in both speculative storytelling and excavation of the game's future plot while adhering to canonical truth. This blending -- an example of what Paul Booth has called "narractivity" -- results in theory posts reconstructing the game's canonical narrative and exploring its deliberate ambiguity for lore hypotheses. As to the allure of such fanworks, I argue that the surplus pleasure derived from speculating about the game's rich lore functions as an "informational meta-game," nested within a traditional gaming experience. r/Genshin_Lore, as a digital "community of practice" dedicated to theorizing about lore, has thus gained popularity because it attracts individuals who enjoy this practice (and who might otherwise feel isolated in their enthusiasm for the game's narrative).

In the context of video game studies, this article enhances understanding of how fans engage with and interpret narrative worlds. By examining the practices and norms of a specific fan community, it sheds light on the dynamics of fan culture and the co-creation of meaning within virtual worlds; it also highlights the unique role played by sites like Reddit, which facilitate open knowledge production by their members. And from an autoethnographic perspective, the article offers insights into the personal motivations that drive fan engagement, using my own situatedness to explore r/Genshin_Lore from both an emic and etic point of view. In doing so, I hope not only to provide an insider look at the analytical behaviors lore theorists often employ, but to also demonstrate the way digital communities like r/Genshin_Lore provide a space for like-minded fans to connect with one another.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Josh Mishaw of the Ohio State University, as well as the article's anonymous reviewers, whose insights helped make the final product all the stronger.

Endnotes

[1] Based on estimates made by ActivePlayer.io. See https://activeplayer.io/genshin-impact/

[2] Although other playable characters can eventually be "unlocked" (that is, made available for the player to control).

[3] Barbados the Anemo Archon rules over Mondstadt; Morax the Geo Archon rules over Liyue; Beelzebul the Electro Archon rules over Inazuma; Buer the Dendro Archon rules over Sumeru; Focalors the Hydro Archon rules over Fontaine; Haborym the Pyro Archon rules over Natlan; and the Tsaritsa the cryo Archon rules over Snezhnaya. Note that these names are, for the most part, the archons' "Goetic titles" (demonic names taken from the Ars Goetica), reflecting the game's Gnostic influences. Among the main characters, Barbados is more commonly addressed as "Venti" (the name of his human persona), Morax as "Zhongli" (the name of his human persona); Beelzebul as both the "Raiden Shogun" (her regnal name) and "Ei" (her personal name); Buer as either "Lesser Lord Kusanli" (her regnal name) or "Nahida" (her personal name); Focalors as "Furina" (the name of her humanity-made-manifest); and Haborym as both "Mavuika" (her personal name) and Kiongozi (her Natlanese "Ancient Name").

[4] For example, http://redd.it/13vvets.

[5] For example, http://redd.it/11sb542.

[6] For example, http://redd.it/vgnbl8.

[7] For example, http://redd.it/163qecb.

[8] For example, http://redd.it/zjdk06.

[9] For example, http://redd.it/15ejuhs.

[10] For example, http://redd.it/1c45m8n.

[11] For example, http://redd.it/1ah64yp.

[12] For example, http://redd.it/185olyq.

[13] For example, http://redd.it/16yhzr9/.

[14] For example, http://redd.it/qyxdtt/.

[15] For example, http://redd.it/15espwz/.

[16] For example, http://redd.it/15wnwnv/.

[17] The original post has since been deleted, but much of it was quoted here: https://www.reddit.com/r/Genshin_Lore/comments/10g9i45/comment/j5cu5hb/.

[18] See http://redd.it/17p2x88.

[19] See http://redd.it/t8kee0.

[20] Some lore enthusiasts have also utilized the affordances of fan art to graphically advance theories or present ideas in a decidedly aesthetic and expressive manner (e.g., https://redd.it/1btc7wa/). However, because this sort of "fan art-based inquiry" foregrounds subjective interpretation, it remains an uncommon practice amongst lore enthusiasts.

[21] For example, http://redd.it/1h2t8ja.

[22] Accusations of irrelevant sourcing often occur when members discuss if and how Genshin Impact's lore connects to the lore of other miHoYo games, notably Honkai Impact 3rd (miHoYo, 2016) and Honkai: Star Rail (miHoYo, 2023). While some fans seek a "unified theory" to bring together these games' stories, others prefer understanding each game's lore in isolation. To prevent arguments, the r/Genshin_Lore mods have decreed that threads about Genshin's connections to other miHoYo games can only be posted on Wednesdays.

References

Adams, M. J. (2022). Tech otakus save the world? Gacha, Genshin Impact, and cybernesis. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 188-208. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.199

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2014). Autoethnography. Oxford University Press.

Anderson, K. E. (2015). Ask me anything: What is Reddit? Library Hi Tech News, 32(5), 8-11. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-03-2015-0018

Andriano, A. M. (2024). Enjoying the uncertainty: How Dark Souls performs incompleteness through narrative, level design and gameplay. Games and Culture. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120241226837

Astle, A. (2024). Genshin Impact hits $6.3 billion in time for fourth anniversary, but is it running on fumes? Pocket Gamer. https://www.pocketgamer.biz/genshin-impact-hits-63-billion-in-time-for-fourth-anniversary-but-is-it-running-on-fumes/

Augustyn, A. (Ed.). (2011). American literature: From the 1850s to 1945. Britannica Educational Publishing.

Ball, K. D. (2017). Fan labor, speculative fiction, and video game lore in the Bloodborne community. Transformative Works and Cultures, 25. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2017.01156

Bembeneck, E. J. (2015). Game, narrative and storyworld in League of Legends. In M. W. Kapell (Ed.), The play versus story divide in game studies (pp. 41-56). McFarland & Company.

Boellstorff, T. (2008). Coming of age in Second Life. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77h1s

Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B. A., Pearce, C., & Taylor, T. L. (2012). Ethnography and virtual worlds. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.cttq9s20

Booth, P. (2009). Narractivity and the narrative database. Narrative Inquiry, 19(2), 372-392. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.19.2.09boo

Bordwell, D. (1989). Making meaning inference and rhetoric in the interpretation of cinema. Harvard University Press.

Brewer, J. (2000). Ethnography. Open University Press.

Cantallops, M. M., & Sicilia, M. A. (2016). Motivations to read and learn in videogame lore: The case of League of Legends. In García-Peñalvo, F. J. (Ed.), Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (pp. 585-591). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3012430.3012578

Crack. (2024, December 9). In Fanlore. https://fanlore.org/w/index.php?title=Crack&oldid=2709985

de Amo, J. M., & Garcia-Roca, A. (2021). Mechanisms for interpretative cooperation: Fan theories in virtual communities. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 699976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.699976

Dooley, B., & Mozur, P. (2022). Beating Japan at its own (video) game: A smash hit From China. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/16/business/genshin-impact-china-japan.html

Eco, U. (1989). The open work (A. Cancogni, Trans.). Harvard Univeristy Press.

Ellis, C. (1997). Evocative autoethnography: Writing emotionally about our lives. In W. G. Tierney & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text (pp. 115-142). State University of New York Press.

Ellis, C. (1999). Heartful autoethnography. Qualitative health research, 9(5), 669-683.

Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. AltaMira Press.

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research-Historische Sozialforschung, 36(4), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589

Elstermann, A. (2023). Participatory storytelling. In Digital literature and critical theory (pp. 79-128). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003361909-4

Ferguson, A. (2022). SCP Foundation (2008-) / Collaborative canons. In I. Yoshinaga, S. Guynes, & G. Canavan (Eds.), Uneven futures: Strategies for community survival from speculative fiction (pp. 119-126). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14093.003.0019

Ferguson, S. L. (1998). Drawing fictional lines: Dialect and narrative in the Victorian novel. Style, 32(1), 1-17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42946406

Fiske, J. (1989). Understanding popular culture. Routledge.

Ford, D. (2021). The haunting of ancient societies in the Mass Effect trilogy and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 21(4). https://gamestudies.org/2104/articles/dom_ford

Ford, D. (2024). Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls games as myth. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 6(3), 31-66. https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v6i3.2175

Fonstad, K. W. (2006). Writing 'to' the map. Tolkien Studies, 3(1), 133-136. https://doi.org/10.1353/tks.2006.0018

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The interpretation of cultures (pp. 3-30). Basic Books.

Geertz, C. (1974). "From the native's point of view": On the nature of anthropological understanding. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 28(1), 26-45.

Geiger, R. S., & Ribes, D. (2011). Trace ethnography: Following coordination through documentary practices. In R. H. Sprague (Ed.), Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2011.455

Gouvea, L. C., Garcia, A. C. B., & Vivacqua, A. S. (2019). Behavior indicators for sensemaking of online discussions. In M. P. Fanti, M. Zhou, D. B. Goldgof, & R. Roberts (Eds.), IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (pp. 1366-1371). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SMC.2019.8914182

Green, J., & Jenkins, H. (2011). Spreadable media. In V. Nightingale (Ed.), The handbook of media audiences (pp. 109-127). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444340525.ch5

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language (pp. 117-127). Routledge.

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2019). Ethnography (4th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315146027

Hills, M. (2002). Fan cultures. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203361337

Hills, M. (2015). The expertise of digital fandom as a 'community of practice.' Convergence, 21(3), 360-374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515579844

Hine, C. (2015). Ethnography for the internet. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474218900

Jain, S. (2023). Genshin Impact's entire plot until Sumeru, explained. The Gamer. https://www.thegamer.com/genshin-impact-entire-plot-explained/

Jansen, D. (2018). A universe divided: Texts vs. games in The Elder Scrolls. DiGRA Nordic ’18: Proceedings of 2018 International DiGRA Nordic Conference. 2018 International DiGRA Nordic Conference, Bergen, Norway. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/1057

Jansen, D. (2021). The final word? How fans of The Elder Scrolls record, archive, and interpret the Battle of Red Mountain. In C. E. Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, K. H. J. Boom, A. A. A. Mol, B. Van Hout, & A. Politopoulos (Eds.), Return to the interactive past. Interactive Past Conference, Leiden, Netherlands. Sidestone Press.

Jemielniak, D. (2014). Common knowledge? An ethnography of Wikipedia. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804791205

Jenkins, A. (2020). Lighting the bonfire: The role of online fan community discourse and collaboration in Dark Souls 3. In G. S. Hubbell (Ed.), What is a game? (pp. 131-146). McFarland & Company.

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203361917

Jenkins, H. (2004) Game design as narrative architecture. In N. Wardrip & P. Harringan (Eds.), First person (pp. 118-130). The MIT Press.

Jones, J. (2022). Exploring the SCP Wiki: Community, digital horror, and apocalyptic fiction (Publication No. 2789971402). [Master's thesis, the University of Texas at Arlington]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Jones, S. H., Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of autoethnography (Original ed.). Routledge.

Kozinets, R. V. (2020). Netnography (3rd ed.). Sage.

Kozinets, R. V., & Kedzior, R. (2009). I, avatar: Auto-netnographic research in virtual worlds. In M. Solomon & N. Wood (Eds.), Virtual social identity and consumer behavior (pp. 3-19). M. E. Sharpe.

Krzywinska, T. (2008). World creation and lore: World of Warcraft as rich text. In H. G. Corneliussen & J. W. Rettberg (Eds.), Digital culture, play, and identity (pp. 123-141). The MIT Press.

Larsen, K., & Zubernis, L. (2011). Fandom at the crossroads. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lim, W. H., Carman, M. J., & Wong, S.-M. J. (2017). Estimating relative user expertise for content quality prediction on Reddit. In P. Dolog, P. Vojtas, F. Bonchi, & D. Helic (Eds.), Proceedings of the 28th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (pp. 55-64). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3078714.3078720

Lum, P. (2020). Genshin Impact: The video game that's slowly taking over the world. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2020/oct/22/genshin-impact-video-game-slowly-taking-over-the-world

Magpantay, A. (2022). Fandom.com and fan-made histories. Transformative Works and Cultures, 37. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2022.2121

Massanari, A. L. (2015). Participatory culture, community, and play: Learning from Reddit. Peter Lang.

McCullough, H. (2022): SCP Foundation Wiki, https://scp-wiki.wikidot.com/. American Journalism, 239-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/08821127.2022.2064167

miHoYo. (v. 8.0, 2025) [2016]. Honkai Impact: 3rd [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game produced by Cai Haoyu and David Jiang, published by HoYoverse.

miHoYo. (v. 5.4, 2025) [2020]. Genshin Impact [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by Liu Wei et al., published by HoYoverse.

miHoYo. (v. 2.7, 2024) [2023]. Honkai: Star Rail [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game produced by David Jiang, published by HoYoverse.

Mittell, J. (2015). Complex TV: The poetics of contemporary television storytelling. NYU Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814744963.001.0001

Mittell, J. (2020). Forensic fandom and the drillable text. Spreadable Media. https://spreadablemedia.org/essays/mittell/index.html#.XuD8KETP32c

Monaco, J. (2010). Memory work, autoethnography and the construction of a fan-ethnography. Participations, 7(1), 102-142.

Morini, V., Pollacci, L., & Rossetti, G. (2021). Toward a standard approach for echo chamber detection: Reddit case study. Applied Sciences, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/app11125390

Nardi, B. A. (2010). My life as a night elf priest: An anthropological account of World of Warcraft. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/toi.8008655.0001.001

Overstreet, M. (2015). Metapragmatics. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 1-6). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1470

Parsakia, K., & Jafari, M. (2023). The dynamics of online fandom communities. AI and Tech in Behavioral and Social Sciences, 1(3), 4-11. https://doi.org/10.61838/kman.aitech.1.3.2

Pearce, C. (2011). Communities of play: Emergent cultures in multiplayer games and virtual worlds. MIT Press.

Polasek, A. D. (2014). Winning 'The Grand Game.' In L. E. Stein & K. Busse (Eds.), Sherlock and transmedia fandom (pp. 41-55). McFarland & Co.

Popova, M. (2020). Follow the trope: A digital (auto)ethnography for fan studies. Transformative Works and Cultures, 33. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2020.1697

Puri, A. (2007). The web of insights: The art and practice of webnography. International Journal of Market Research, 49(3), 387-408. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530704900308

Reinhard, A. D. (2018). Archaeogaming. Berghahn Books.

Reinhard, A. D. (2019). Archaeology of digital environments [Doctoral dissertation, University of York]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1056111

Reysen, S., Plante, C., & Chadborn, D. (2017). Better together: Social connections mediate the relationship between fandom and well-being. AASCIT Journal of Health, 4(6), 68-73.

Reysen, S., Plante, C. N., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2022). Social activities mediate the relation between fandom identification and psychological well-being. Leisure Sciences, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2021.2023714

Rieber, L. P., Smith, L., & Noah, D. (1998). The value of serious play. Educational Technology, 38(6), 29-37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44428495

Royte, D. (2024). miHoYo enters top 15 largest private companies. AFK Gaming. https://afkgaming.com/gaming/genshin-impact/mihoyo-enters-top-15-largest-private-companies-the-genshin-impact-dev-is-valued-at-23-billion

Sandro, S. W. (2020). 近年のドイツ映画の日本語字幕における異文化要素の翻訳方略 [Translation strategies for cross-cultural elements in Japanese subtitles of recent German films]. Essay series on modern language and modern culture, 21, 33-62.

Schniz, F. (2016). Skeptical hunter(s): A critical approach to the cryptic ludonarrative of Bloodborne and its player community [Conference presentation]. The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Malta.

Silverstein, M. (2022). Language in culture (E. S. Carr, S. Gal, & C. V. Nakassis, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009198813

Spradley, J. P. (2016a). The ethnographic interview. Waveland Press.

Spradley, J. P. (2016b). Participant observation. Waveland Press.

Taylor, T. L. (2009). Play between worlds. MIT Press.

Thomas, P. A. (2018). Canon wars: A semiotic and ethnographic study of a Wikipedia talk page debate concerning the canon of Star Wars. The Journal of Fandom Studies, 6(3), 279-300. https://doi.org/10.1386/jfs.6.3.279_1

Tremblay, K. (2023). Collaborative worldbuilding for video games. CRC Press.

Tulloch, J., & Alvarado, M. (1983). Doctor Who: The unfolding text. St. Martin's Press.

van de Mosselaer, N., & Gualeni, S. (2023). The implied designer of digital games. Estetika, LX/XVI(1), 71-89. https://doi.org/10.33134/eeja.303

van Stegeren, J. (2022). Flavor text generation for role-playing video games (SIKS Dissertation Series no. 2022-1; DSI Ph.D. Thesis Series No. 22-001). Digital Society Institute at the University of Twente. https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789036553100

Westman, K. E. (2022). Realism and race: The narrative politics of Harry Potter. In S. P. Dahlen & E. E. Thomas (Eds.), Harry Potter and the Other (pp. 51-70). University Press of Mississippi. https://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781496840578.003.0003

Zygutis, L. (2021). Affirmational canons and transformative literature: Notes on teaching with fandom. Transformative Works and Cultures, 35. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2021.1917