Labyrinths and remediation: the birth and resolution of the humanist subject in the video game Pentiment

by Zsófia O. RétiAbstract

Obsidian Entertainment’s 2022 detective game Pentiment is an unorthodox take on the trope of the Middle Ages in video games. With its codex-like visuals, it does not build on an illusion of immediacy and authenticity, as many similarly themed games do, but instead explicitly addresses the text-based nature of any knowledge available about the age. With a nod to not only manuscript culture but also one of the most famous postmodern literary works that focuses on the same period, Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Pentiment is preoccupied with mazes -- both at a thematic and a structural-game mechanical level. This article looks at the way various labyrinthine structures are used in the game to simulate the emergence of the humanist subject, which was directly affected by the spread of the printing press. Furthermore, by relying on the model of remediation developed by Bolter and Grusin, it also proposes that the game creates rhizomatic structures -- a very different kind of maze -- through the hypermediation of manuscripts. Such hypermediated rhizomes enable the silenced Others of the white male humanist subject -- women and people of colour -- to find their voice.

Keywords: medieval games, hypermediation, remediation, rhizome, labyrinth, Name of the Rose, Pentiment, humanism, posthumanism

Introduction: Intermedial Mazes

The text conceived as a labyrinth has been a defining image of postmodern literature, itself caught in -- or woven of -- a web of inevitable intertextuality. The classic example, the Borgesian “Garden of Forking Paths” (Borges, 1962), refers both to the labyrinth as an object and space, and to the novel itself, which also models a labyrinth in its structure (Faris, 1988, p. 10). At the same time, the library -- a collection of books itself -- can sometimes appear as a labyrinthine space, like in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1980), or even as a limitless place with a rich tradition as a symbol of human existence (from Borges’s “The Library of Babel” (Borges, 1998) to Matt Haig’s Midnight Library (Haig, 2020)). Postmodern texts that rely on the theme of the labyrinth are mostly based on genre traditions of the detective story, which as a literary genre presupposes playfulness (Fernández-Vara, 2018). In such pieces, the reader is just as interested in solving the mystery -- an unreal, formulaic puzzle (Bényei, 2000, p. 29) -- as the detective in the text. Like detective stories, textual labyrinths presuppose a certain level of participation, as it is not possible to watch or read a labyrinth without wanting to walk it oneself. Despite its rich and varied symbolism, figurative and actual labyrinth-walking (in all media) is an active action of essentially ludic nature.

Obsidian Entertainment’s 2022 codex-inspired detective game Pentiment transports the player to Bavaria in the first half of the 16th century. The game considers both the cultural connotations and playful potential of labyrinths, in addition to their textual and bookish associations. The game adopts a visual style that resembles medieval illuminated manuscripts and even stages the plot of the game as a story that is included within the pages of a codex. The plot follows an artist visiting a Benedictine monastery and investigating a murder case in the process. In the following analysis, I place Pentiment in the context of medieval games and remediation to argue that the game simulates the emergence of the humanist subject in the wake of 16th century technomedial changes: the shift from a predominantly manuscript-based culture to one that is shaped by the spread of the printing press. However, in doing so through the hypermediation of codices, the game creates rhizome-like structures in which the stories of culturally othered women and people of colour are also given voice. These stories, which are typically silenced or ignored in other medieval-themed video games, undermine the very hegemony of this humanist subject. To this end, I apply a close reading analysis to look at Pentiment’s game mechanics alongside its narrative-thematic levels, focusing on the game’s time management techniques and the tension it creates between originality and tradition. By analysing the role of remediated labyrinths at various diegetic levels of the game, I trace how the game stages the emergence of the humanist subject and produces rhizomes that also permit anti-canonical speech positions to emerge. Finally, further drawing on Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s concept of remediation, I illustrate how the marked visibility of the medial shift enables agents to act and counter-memories to emerge in ways that have been previously obscured by the triumph of the humanist subject.

Mediated Medievalism

While Pentiment is set in the 16th century, technically well into the Renaissance period, it simulates the shift from medieval to Renaissance sensibilities in terms of epistemologies and ontologies. It is interesting to compare Pentiment with traditional, medieval themed video games. Although Pentiment offers a rather unique take on the late Middle Ages, the historical period as a subject matter of both popular culture in general and video games in particular has been quite popular in the last few decades. As early as 1986, Umberto Eco noted an obsessive drive in modern culture to return to the medieval period, basically from the moment that it came to an end -- a process that Eco ascribes to the fact that Modern consciousness was directly shaped by medieval sensibilities and societal conditions (Eco, 1995, pp. 63-65). In a similar fashion, fantasy author Lev Grossman greeted the release of The Lord of the Rings film and the resurgence of the medieval fantasy genre that he saw as a counterpoint to sci-fi imaginaries in 2002, suggesting that the new-found popularity of the genre was caused by a novel mistrust in technological advancements and a desire for simple, more authentic times (Grossman, Billips, & Schultz, 2002). With this context in mind, it seems that a long-standing interest in the Middle Ages combined with a 21st century yearning for uncorrupted immediacy arguably produced a new surge in medieval-themed products in popular culture.

This trend is observable in video games: as César San Nicolás Romera and his research group contend, between 2003 and 2013 some five hundred medieval-themed video games were released worldwide, showing a very clear predominance of the genre in the game industry (San Nicolás Romera, Nicolás Ojeda, & Ros Velasco, 2018, p. 522). This sample is in line with what the industry typically regards as medieval themed game and includes both purely historical and medieval fantasy settings. A common trait among these games is that they often make claims to historical authenticity and realism. This seems to be a requirement of medieval themed games even more so than in historical games in general (Houghton, 2024). This realism, based on Adam Chapman’s classification, can either take the form of conceptual or realist simulation (Chapman, 2016, p. 61, 69). While the former demonstrates the mechanics or an era through procedural rhetorics, the latter relies on showing what a certain period looked like and heavily relies on sound and graphics. One of the most well-known medieval games, Kingdom Come: Deliverance, was distinctly marketed with such rhetoric of audiovisual authenticity, as seen in its Kickstarter caption which reads “Dungeons & no Dragons” (Bostal, 2019, p. 382). The game established a distinct cinematic fighting style that Robert Houghton dubs “brutal medievalist combat” (Houghton, 2024). At the same time, most scholarship about the contemporary fascination with the Middle Ages highlights that contemporary fantasies of medieval times are shaped by popular culture, Tolkien, Disney, Monty Python, etc. (Cooper, 2019). This is the template that Umberto Eco calls hyperreality: in our desperate postmodern desire to get a better grasp on reality, we “must fabricate the absolute fake” to conceal the shaky edifice of reality (Eco, 1995, p. 8). In this sense, medievalism as pop cultural praxis and medievalism as scientific field certainly share one similarity: they both heavily rely on textual documentation of the past. Josh Sawyer, the writer of Pentiment, quotes British historical novelist Hilary Mantel when defining his approach: “It’s the record of what’s left on the record” (Alvis, 2022), hence the inherently fragmentary and mediatised nature of all knowledge that one can acquire regarding the past. Pentiment, much like the recent title Inkulinati (Yaza, 2023), goes against this general trend of realistic visual representations in favour of a deliberate and explicit reliance on manuscript culture to fascinate the “player-historian” (Chapman, 2016, p. 22). In this sense, the kind of historical authenticity that Pentiment propagates “foregrounds the subjective, constructed nature of history and the consequences of the decisions made in the process,” as it takes into account an idea that the only authentic take on history is one with a multitude of voices and layers and a great deal of uncertainty (Wright, 2024).

Pentiment adopts an unconventional, “hypermediated” depiction of a historical moment when the 16th century media landscape was in major flux. As such, Bolter and Grusin's theory of remediation can help make sense of Pentiment’s liberating potential. Remediation, the process of one recent medium interacting with other, previous media is characterised by the dynamic interplay of two contradictory modes: transparent immediacy and opaque hypermediacy (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 5.). Transparent immediacy, by “ignoring or denying the presence of the medium and the act of mediation,” seeks to produce a more authentic experience (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 11) through linear perspective, erasure and automacity (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 26). In contrast, opaque hypermediacy invites “us to take pleasure in the act of mediation” (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 14) through the visually fragmented, “windowed” style that, according to Bolter and Grusin, is so typical of the Y2K digital landscape (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 31) -- and remains prevalent today in new media.

Bolter and Grusin offer examples of both immediacy and hypermediacy from earlier historical periods, such as the medieval manuscript as a case of hypermediation. They predominantly gear their arguments to new media forms, with a specific chapter dedicated to the “essentially adaptive” (Corbett, 2009, p. 11) world of video games -- which repurposes earlier codes of cinema, board games and sports (Perron, Montembeault, Morin-Simard, & Therrien, 2019, p. 37). Although Bolter and Grusin present a balanced view of hypermediacy and immediacy in games, there is a current trend -- both in the industry and the academia -- to put more emphasis on the desire of video games for immediacy (Ivănescu, 2019, p. 29), rooted in what Ewan Kirkland calls “the lack of the ‘real’ in digital media” (Kirkland, 2009, p. 116). Understandably, the centre stage of this ever-expanding field is taken by the dynamics of remediation between video games and films (Girina, 2013; Perron et al., 2019), with occasional inquiries into theatre and video games (Corbett, 2009), literature and video games (Caracciolo, 2023), or analogue media technologies in the horror subgenre (Kirkland, 2009).

Still, for obvious reasons -- i.e., the lack of relevant examples before 2023 -- the remediation of late medieval codex culture and the early Renaissance printing press has remained unexplored in video games. The medieval-Renaissance medial shift relied on a technological innovation that brought along more democratic access to knowledge and culture and set the ground for all kinds of cultural revolutions such as the Reformation. At the same time, the production and distribution of knowledge received a significant boost: a kind of “knowledge industry” was in formation (Eisenstein, 1980, p. 116). The expansion of knowledge and the democratization of access to it definitely resonates well with the media landscape of the early 21st century, where the emergence of new media had a similar effect on the dissemination of information (Sawday & Rhodes, 2002). As Bolter and Grusin contend, Western culture’s fascination with immediacy and hence the interplay between hypermediacy and immediacy can also be traced back to the Renaissance visual innovation of linear perspective (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 23). Ultimately, both the early Renaissance and the 21st century made it possible for a new stratum of society to access knowledge and make their voices heard, and in the following, I would like to highlight how hypermediacy plays a pivotal role in that.

The Birth of the Humanist Subject

The creation of Pentiment was preceded by much more and different research than is usual for historical video games (Hafer, 2022; Watts, 2022), covering not only the object culture of the 16th century but also the cultural history of the late medieval to early modern period. The title of the game, derived from the Italian term pentimento, relates to the act of repentance but also refers to the first version of a work of art emerging from beneath a top layer of paint, which is a motif that can be traced throughout the entire game. Pentiment is the story of three investigations over a combined period of thirty years, each investigation lasting roughly five hours of gameplay. In the first investigation, the player controls the young artist Andreas Maler, who arrives in Tassing in 1518 to try to complete his masterpiece, an illustration of a book of hours. In pursuing his work, he joins the monks in the scriptorium of Kiersau Abbey -- them copying codices, Andreas painting the book of hours. There are obvious parallels to Eco’s The Name of the Rose, where an investigation is also started by an outsider character. In fact, Pentiment opens with the image of a manuscript page featuring the Latin translation of a passage from the novel, which the player has to erase with a pumice stone to be able to start playing (Kleinermann-Haynes, 2023). The game is also related to Eco’s work in its emphasis on written textuality: instead of speaking vocally, the conversations are presented in speech bubbles, where the font type reflects the social standing and dialect of the character or Andreas’s opinion of them (Schild, 2023). The characters “speak” in simplified or scrawled Gothic letters, or in the case of the printer, in neatly (upside-down) stencilled impressions of early book printing. Additionally, whenever characters are experiencing strong emotions, they make mistakes and splotch their manuscript texts; after careful scraping, they correct spelling mistakes in a palimpsest-like manner.

When the abbey’s patron, the baron Lorenz Rothwogel, arrives in Tassing, he quickly befriends the cultured Andreas, considering him as an intellectual partner. When the baron is murdered, the artist takes it upon himself to investigate the case and prove the innocence of his mentor Piero. The player’s task is to identify the murderer in a limited amount of time. The second investigation takes place seven years later, when Andreas returns to the abbey as a master with his apprentice Caspar. When Otto, the leader of the Tassing peasant rebellion, is found dead, Andreas starts another investigation: this time to save the lives of the mostly innocent monks from the angry villagers. Regardless of the player’s decisions, the investigation ends with the peasants setting the library and scriptorium on fire -- a plot point also seemingly borrowed from The Name of the Rose. Andreas Maler is last seen rushing into the burning library to rescue as many manuscripts as possible. The third part of the game takes place seventeen years later, this time with the player-controlled character Magdalene Druckeryn, daughter of the printer of Tassing, who lived through the destruction of the abbey as a small child. After her father’s injury, she begins her own investigation by gathering information about the history of the town for a fresco in the town hall. She uses a very similar methodology to Andreas during his murder investigations: asking around the village for useful information, listening to what everyone has to say, dedicating some time to explore certain spaces, etc. By the end of the game, it becomes clear that Andreas has been hiding in Tassing all along. He and Magda descend into the Roman ruins beneath the town to reveal the layered, conflicting history of Tassing, which also uncovers deeper motivations that lie beneath the murders. “Pentimento” can thus refer not only to the works of art superimposed on each other, but also to the plot’s overlapping investigations and each character’s conflicting conceptions of the past.

At the same time, Pentiment simulates the epistemic change between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, mostly through the influence of book printing, building on technological determinism. Marshall McLuhan has made the assertion that book printing brought about substantial and anthropological changes (McLuhan, ([1964], 2003). While often criticized for unfounded observations (Eisenstein, 1980; Kittler, 2001), his work is still seminal when it comes to making sense about the medieval-renaissance shift. McLuhan points out that the phonetic alphabet, which was essential for book printing, made the spread of the mechanical clock possible. This technology created a novel way of measuring time more precisely, by dividing days into standard units of equal length (McLuhan, 2003, p. 202). This shift in the treatment of time is reflected in Pentiment as well. In the first and second parts the game, Andreas’s investigation and the passage of time are determined by the rhythm of medieval life measured by prayer and meals (much like in The Name of The Rose). In the game, time is a resource, and some (but not all) phases of the investigation require time. For example, a meal might be devoted to talking to someone over the food, or a morning/afternoon might be spent listening to confessions, or helping the weaving women in case something relevant is said in their conversation. At such times, the sun, visualised as a wheel, constantly reminds the player of the time that is about to run out. By contrast, in the third part of the game, Magdalene is not constrained by the imperative of ora et labora. Although time does pass during her actions, it is now marked by an astronomical clock, capable of accurately measuring multiple units of time -- hours, minutes, weeks, months -- and indicating twenty-four hours, thus illustrating not only the rhythm of the days but also the quantifiable linear progression of time.

The shift from circularity to progression is also a central theme of Pentiment as it relates to medieval and Renaissance tradition. Handwritten, expensive and rare, codices were all about faithfully preserving the knowledge handed down from the ancients, just as much of medieval culture was focused on maintaining the continuity of collective memory. Visuality was in service to memory, for example in the medieval practice of the memory palace. Memory palaces involved imagining one’s mind as an actual space, and evoked information by connecting it to specific locations within their memory palace. But the printing press brought about an age in which such trainings of memory, or even “servile duplication” itself, were less necessary, as the same texts became more widely available. At the same time, a multitude of readers could discover the errors in a printed text. Even the publication of errata became possible, which was closely connected to the essentially scientific, fact-checking disposition of the Renaissance man (Eisenstein, 1980, p. 85). With the spread of the printing press, the necessarily conservative attitude of medieval culture and the need for perfect preservation and revelation of the past gave way to a conviction that the individual was unique, and that change was possible and necessary. In Pentiment, the most interesting example of this is Andreas’s masterpiece in progress, which happens to be an illustration for a book of hours. In its first version, Andreas illustrates a November scene of peasants gathering acorns in the forest. “It’s an excellent interpretation of someone else’s work,” says Piero, Andreas’s elderly mentor. “It’s … November. In November we show peasants leading the pigs into the forest to forage on acorns before the slaughter,” argues Andreas, whereupon Piero points out that the abbot of the Kiersau Abbey, among others, had forbidden peasants to graze pigs in the forest. “What difference does it make? This is the way November is painted,” Andreas explains, but the finished masterpiece shows that he has taken Piero’s advice. The sketch of peasants in the woods is presented here as a pentimento that is obscured by the final version, in which the same figures are now driving the pigs in the fields, next to the fenced-off woods.

Piero clearly associates this shift with the artist’s need to make himself visible in the process of creation -- that is, he insists on the importance of innovation and self-expression alongside tradition and preservation. This is the kind of a change that Elisabeth Eisenstein attributes to the reproducibility guaranteed by the printing press. While the medieval scribe had no way of showing his own individual peculiarities in the text he copied (Eisenstein, 1980, p. 229), copying literally implied giving faces. Certain facial features were increasingly associated with certain authors. Likewise, depictions of faces were not linked to names of particular artists, and thus were not individuated (Eisenstein, 1980, p. 233). In line with this, Andreas had his semblance imprinted on the final version of his masterpiece.

The birth of the modern (authorial) subject comes with a price: perfect preservation and reconstruction of the past becomes impossible. Pentiment plays with this insight at the level of game mechanics. Across the first and second chapters of the game, Andreas’s two murder investigations implicate several possible perpetrators. As it turns out, someone has manipulated both cases with messages scrawled in Gothic letters, muddying the investigation such that the murderer is never brought to justice. In the first investigation, every suspect has understandable and even excusable reasons for committing the crime, meaning that they are morally exonerated. In the second investigation, all suspects are portrayed as vile, fallible characters, yet none of them could have committed the murder. Moreover, the game’s progression demands that someone must be named as the culprit, but the player character receives no feedback as to who actually committed the murder, so they cannot be absolutely certain in their choice. The third investigation, in which Magdalene tries to unravel the story of Tassing, differs from this pattern in that it is not about uncovering a singular truth, but rather about choosing from among competing past constructions that are equally relevant to the history of the city. At one extreme is the scriptorium, which, as several characters refer to it, is a “place outside time” -- that is, a place of “cold memory” as Jan Assmann, building upon Claude Lévi-Strauss’s terminology, would call it. Magdalene’s project, on the other hand, is based on selective memory associated with one particular view of the past -- one “characterized by ‘an avid need for change,’ [which has] internalized [its] history (…) in order to make it the driving force behind their development” (Assmann, 2011, p. 54). By contrast, “hot memory,” defines relationships with the past in light of what aspects are relevant to the present.

This also relates to the destruction of the library. The leader of the peasants burns it down specifically because, in his own words, if the library remains, “nothing will ever change.” This is, after all, the age of peasant rebellions alongside the spread of book printing, and the game posits a direct link between the two: the widespread dissemination of knowledge and ideas made possible rapid and radical, often grassroots, changes.

Mental Labyrinths

The epistemic shift in Pentiment is well demonstrated by the labyrinths that appear at three points in the game. Each are presented in Andreas’s dreams as city spaces that allegorize the player character’s mind. As Penelope Reed Doob demonstrates, the labyrinth in medieval thought is an allegory of human life, whose winding path often leads to unexpected places (Doob, 2019, p. 120), and may seem random and full of adversity to the person wandering within it. The perspective-dependent paradox of the labyrinth is that what appears to be disorderly chaos from the inside is a cleverly conceived system when observed from above, exemplifying both the deliberation and genius of its creator (Doob, 2019, p. 29). This implies that, until the 16th century, labyrinths were invariably unicursal. Though they were long and meandering, there was no way to get lost in them, clearly allegorising the position of man placing control of his life in the hands of God.

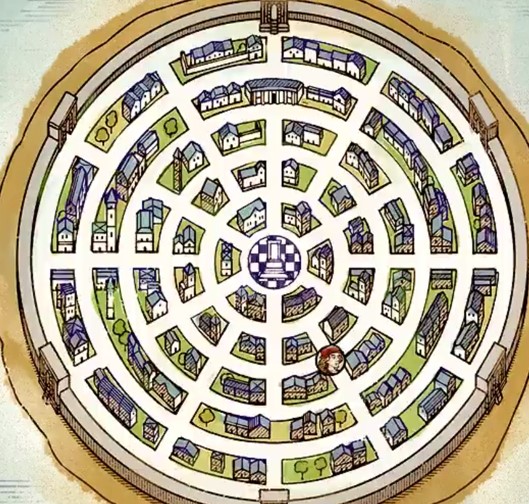

In the first third of the game, the mental city of the young adult Andreas is not a labyrinth in this sense, but a series of streets in concentric circles, presented from a top-down view, as seen in Figure 1. Here the player can lead Andreas toward the main square of the city, where he is met with three allegorical figures that symbolize three aspects of his mind: Prester John (intellect), Beatrice (curiosity) and Saint Grobian (irrationality).

Figure 1. Andreas's first labyrinth. Click image to enlarge.

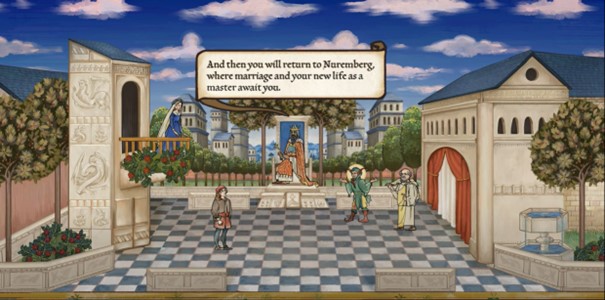

It is noteworthy that after the main title, Pentiment immediately places the player-controlled Andreas in this allegorical space. In this dreamscape, Andreas stands within pages of a realistically rendered manuscript, which inform the player about the date and setting. After the player sees an image of the sleeping Andreas (“The artist sleeps”) on the codex pages, the next image (“An artist’s mind”) fills the entire screen, and the player can take control of Andreas (his responses).

Figure 2. The centre of Andreas's labyrinth. Click image to enlarge.

This zeroth “labyrinth” through which the player arrives, not only in Andreas’s mind but also in the game itself, is thus a spectacular interweaving of different types of media texts -- a hypermediation that encourages the recipient to recognize the pleasure of the media shift (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 14).

In the second part, set in 1525, we meet an Andreas who has not only become a successful artist, but whose life has been full of losses and regrets. Accordingly, the actual unicursal labyrinth in the dream sequence is now accompanied by more physically demanding game mechanics, as the player, if playing on PC, must keep the left mouse button pressed while guiding Andreas's icon through the labyrinth. Meanwhile, the ghosts of Andreas’s past -- his wife, whom he left without a word, his young son, whom he failed to save from the plague -- keep getting in his way. In this context, the labyrinth is still an allegory of man’s difficult journey, and as Andreas grows older, the labyrinths become more and more tortuous and difficult to understand.

The third part, set in 1545, is in line with the Renaissance mindset in its representation of the maze. Although the “gardens of forking paths” -- that is, the multicursal maze leading to potential dead ends -- appears as a textual construct from antiquity, its visual representation would not appear until the 16th century. The advent of the multicursal labyrinth is of philosophical significance in the cultural history of the early modern period, as it models perfectly how individuals can easily find themselves caught in a dead end but promotes personal choice and agency. If things go wrong within a system perfectly designed by a higher power, it is the result of the subject’s free, but possibly ill-conceived, choice -- much like in video games which often create seductive illusions of agency.

Figure 3. The third labyrinth. Click image to enlarge.

Andreas’ third mental labyrinth can be seen as a reflection of his mistakes. By now, the player-controlled character has been wracked by guilt for decades, as the game mechanics inevitably lead him to blame himself for the deaths of two to four innocent people depending on the player’s choices. This time, the maze does not take the form of a town square, but is a flaming, unreal space surrounding a gaping, demented demon face. The direction of movement is also different: the circular icon representing Andreas must be brought to the exit instead of the heart of the labyrinth. Progress is occasionally halted when Andreas is confronted with the monsters of his own making, the monsters of regret who otherwise always acquit him. Controlling the game becomes even more difficult: this time the player must not only hold down the mouse button but constantly drag it in a direction to make Andreas move. The maze is full of dead ends, and the layout also changes from time to time, so that Andreas repeatedly finds himself trapped.

This last labyrinth differs from the previous two in that it is not framed as a dream and thus is not clearly separated from the diegetic level of the investigation. At the end of the game, Andreas and Magdalene set off together, in search of the mysterious Mithraeum, the underground sanctuary of the god Mithras. They begin by exploring the already labyrinthine Roman ruins beneath the Rathaus. According to the logic of the game, this is the heart of the labyrinth, where the key to the mystery awaits. As Andreas and Magdalene wander, they must pass through the hypocaust, a ventilation system used in Roman times to heat the room above by circulating air among equally spaced columns. The hypocaust creates an unintended labyrinth, and it is here that Magdalene and Andreas are separated. From this point on, the player controls Andreas alone, who, amidst the ever-increasing shaking of the screen, can already hear (as the player reads) the accusatory words of Baron Rothwogel and the townspeople that he condemned to death, all while walking among the pillars of the hypocaust. This is how the player arrives at the flaming main square of Andreas’s mind, where St. Grobian is now a giant, drumming and tearing down the tower of a city -- hence the constant shaking in the hypocaust. The labyrinth here is clearly conceived in the context of different diegetic levels and layered medial-cultural transmissions. When Andreas is about to emerge from his mental labyrinth, his guide Beatrice, an allegory of curiosity, warns him: “this next part might be confusing.”

Suddenly, the surroundings of the maze disappear and transform into the maze held by the Mary icon of the church of Tassing, this time in the form of Beatrice. “There are layers to everything,” Beatrice reminds Andreas, “even our memories. Over time, the foundations became buried. We can no longer recall how we got here, no longer recall what came before.” Beatrice’s image then peels away from Our Lady, who also turns to ash to reveal the face of Sister Amalie, holding the head of the god Mars: she mentions that she miraculously found herself at the Mithraeum/tabernaculum, the heart of the labyrinthine network beneath the city and the key to solving the mysteries. This merging of diegetic levels is confirmed by Sister Amalie herself, an anchoress: in a walled cell attached to the temple, she awaits the visions and death sent to her by God. For her, as a mystic, the wandering body and of the wandering mind are indistinguishable: while she has actually visited this secret place through her cell, she is convinced that only her soul has been led there, in a vision. In a dialogue option, she explains the vision by saying that the act of reading -- that is, mediated experience -- cannot convey spiritual truth. This contrasts with the hypermediated labyrinth at the beginning of the game, in which layered medial levels foreground a spectacular account of their own presence. By contrast, the labyrinth at the end of the game presents a fantasy of immediacy and transparency -- the idea that one might access truth directly, without mediation. This fantasy is presented as an unsettling possibility within the game as it blurs the boundaries between vision, memory and material reality. It echoes what Bolter and Grusin describe as, “the notion that a medium could erase itself and leave the viewer in the presence of the objects represented, so that he could know the objects directly” (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 70). In Pentiment, this collapsing of medial layers evokes the mystical and the revelatory but also raises questions about the reliability of perception and the dangers of erasing historical and interpretive distance.

Consequently, just like in The Name of the Rose, the labyrinth is not only the theme but also the form of Pentiment. In one way, the game is a labyrinth with layers of remediation, but in another, the murder investigation that gives the gameplay its structure can also be seen as a series of forking paths (Burdette, 2022). At any given point, the player character can pursue at least three potential leads, talking to three different people to try to unravel the mysteries. Of course, several of these leads will inevitably be redundant because the game’s time mechanics make it impossible to investigate all clues, such that different playthroughs yield several different narrative paths. It is not simply a question of a branching labyrinth; the interconnected nature of the traversable paths is more accurately described by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s concept of the rhizome (Deleuze and Guattari, 2015). Eco relates the rhizome to a particular kind of labyrinth in which “every point can be connected with every other point,” where the connections are constantly changing and the rhizome cannot therefore be described in its entirety (Eco, 1986, p. 81). It is not difficult to conclude that digital media, including video games, have a fundamentally rhizomatic potential (Fernandez-Vara, 2007, p. 75), and in the case of Pentiment, the investigation itself, as a game mechanic, has rhizomatic structure. The investigation’s feasibility -- that is, the resilience of the network -- is due to the fact that the innumerable edges allow for a near infinite number of entry points. Thus, it is possible to navigate the network even if a significant part of it is not explored by the player: “[a] rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 10).

The notion of the rhizome may also be relevant in how Pentiment remediates manuscript culture. As Eco points out, “[t]he rhizome has its own outside with which it makes another rhizome” (Eco, 1986, p. 81). The prevalent use of hypermediation in Pentiment offers a rhizomatic structure that works in line with what Deleuze and Guattari say about the role of books: “contrary to a deeply rooted belief, the book is not an image of the world. It forms a rhizome with the world, there is an aparallel evolution of the book and the world” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 11). The multiple threads of Pentiment’s investigation create more and more connections with the codex-like fragments included in the game, which are themselves hypermediated, since the ornate initials are also part of the text and invite the reader to interpret the interweaving of image and text (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 12).

Girl Is the Measure of All Things

As shown above, the symbolic and actual navigation of multicursal labyrinths can be interpreted as an allegory for the rational humanist individual capable of defining his own destiny: the homo mensura, or even the subject of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian man, is a human being capable of fully understanding and bending the world at will. As Rosi Braidotti writes, the “Man” of classical humanism is at the top of the evolutionary scale, implying that he defines himself in opposition to those lower down the scale -- those who are different from him -- and finds his voice in contrast to them (Braidotti, 2022, p. 18). This distinction delineates the idea of “being-human” against “those racialized and sexualized human ‘others,’ whose purported affinity with ‘nature’ excludes them from participating to the fullest extent in being human” (Babka et al., 2023). From this point of view, the primacy of the humanist subject, in line with its posthumanist critique, can only be achieved by defining and marginalizing its non-hegemonic Others. Women, LGBTQ+ persons, non-whites, and other marginalized groups are denied their social and symbolic existence (Braidotti, 2022, p. 18), and are socially affiliated with “freaks, animals, and automata” (Ferrando, 2019, p. 26). While the game successfully simulates the medieval-renaissance anthropological transition, it also systematically undermines the hegemony of the early modern individual.

The most obvious evidence of this is the inevitable failure of Andreas’s investigations. Despite his best efforts, he is unable to make sense of the world around him, and his mind becomes increasingly unhinged as the game progresses. In contrast, Magda, the daughter of the printer has been socialised in the science-centred and rational paradigm of the Renaissance. She becomes Andreas’s dutiful, clear-thinking counterpart whose investigation necessarily ends in a successful fresco that helps maintain collective memory. In line with this, the player’s decisions arguably carry much more weight when playing as Magda. The only decision that the player gets to make in relation to Andreas’s life is whether to save his apprentice Caspar or seal his fate. However, if Andreas is kind and caring to Caspar, the boy will not go when Andreas asks him to, which will ultimately cost the boy his life. In the case of Magdalene, on the other hand, the player’s decisions affect whether she gets married and stays in Tassing. Pentiment thus seems to spectacularly deprive the Renaissance human of the agency of spatial movement, rational interpretation and choice -- in favour of his Other, the subordinate woman.

Similarly, the gender of the player character affects the areas of the game world that they can access. It would be obvious to set up a distinction between the scriptorium as a specifically masculine space -- the space of logos -- and the feminine convent, but as the scriptorium is destroyed in the fire at the end of the second part, it becomes inaccessible to all characters. The scales are clearly tipped towards Magdalene, who is not only comfortable in the masculine spaces of the town hall and the tavern, but also has access to the convent simply because of her gender. Andreas’s exclusion from such spaces, which are coded as feminine by 16th-century logic, is illustrated by one of the optional clues in the first third of play. Here, Andreas can help the women of the town make yarn from the shorn wool of sheep, hoping to gain information in the process that will, like Ariadne’s yarn, lead him out of the labyrinth of the murder investigation. While the women gossip among themselves, Andreas can listen through the window but cannot enter the room itself.

Additionally, labyrinths themselves are culturally coded with gender. As Wendy B. Faris points out, the mostly secret, hidden, often subterranean labyrinth is a feminine space by its form and function (Faris, 1988, p. 6). Through this, the male hero reaches his reward, the solution of the mystery. As Mircea Eliade warns, entering the cave or labyrinth is the equivalent of a mystical return to the mother, the womb (Eliade, 1957, p. 228). In line with this is the fact that in Pentiment the labyrinth is held by Beatrice/Mary the Virgin, and the only character Andreas encounters in all three labyrinths is his estranged wife, Sabine.

While this series of labyrinths represents Andreas’s inner journey and transformation into a humanist subject, the game as a hypermediated rhizome raises up stories that are often eclipsed by tales centring the rational, early modern European man. This counter-narrative tendency is especially evident when the player encounters a manuscript: the pages fill the entire screen, and although players cannot scroll or actually read the text, the textuality (and hence mediality) is pronounced and grabs the player’s attention (Vandewalle, 2023).

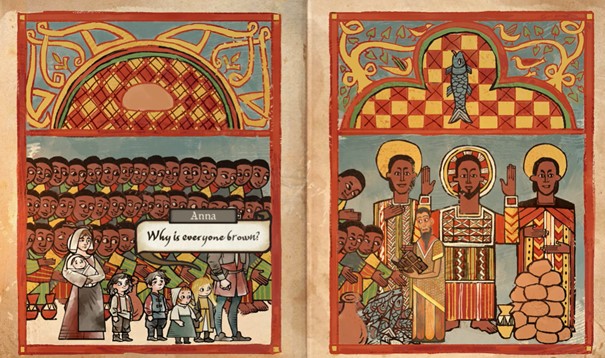

Figure 4. Hypermediation in Brother Sebhat's Bible. Click image to enlarge.

One of the best examples of this is another optional activity in which Andreas can speak with a visiting priest of colour in the abbey named Brother Sebhat from Ethiopia. Sebhat is happy to tell stories to an audience of village women and children, i.e., people in non-hegemonic positions like himself. Storytelling in this case is an explicitly book-mediated activity, where the audience, together with the player, is immersed in a richly illustrated page of the Ethiopian Bible (see Figure 4). While the illustration remains static as a background, Sebhat’s audience is free to move around across the pages or ask questions. Thus, the game reflects on the difference between the underlying assumptions of the audience -- the Bible as a story of white people -- and its representation in a book from a distinctly different culture. “Why is everyone brown?” asks one of the children. “Because where I am from, everyone looks like me,” replies Sebhat. As the conversation continues, the murder of Rothwogel is brought up. Sebhat tries to console the audience with another biblical story, the resurrection of Lazarus. The Ethiopian monk can connect his own Bible, a narrative based on his own traditions, to the main plot and the audience’s experience. He presents the narrative to them in the form of a distinctly hypermediated manuscript pages: not as a labyrinth, but as a rhizome.

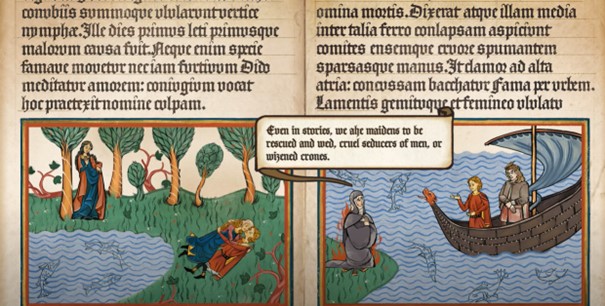

Figure 5. Sister Illuminata as Dido on the pyre. Click image to enlarge.

The codex is also the first place where Pentiment foregrounds the voices of women, figures who have been historically subordinate to the male humanist subject. At the beginning of the game, a nun named Sister Illuminata asks Andreas to return some books from the scriptorium through a small opening cut into the door that separates the convent and the abbey. While the story of Sebhat is only encountered in certain playthroughs, Illuminata’s request is a mandatory element. As Andreas takes the books back, the manuscript page fills the screen (see above). Here, Illuminata and Andreas are not just additions to the original images but take up positions as characters in the illustration and speak to each other from there. The first book to be animated like this is Virgil’s Aeneid, which Illuminata describes as “fine poetry. For men.” Indeed, the epic that traces the journey of the (male) hero does not have many agentic positions for female readers, and within the illustration Illuminata assumes the role of the only available female character, Dido. In the epic, Dido’s main role is to listen to Aeneas’s account. When he abandons her to his duty, she builds a bonfire in grief, on which she ends her life using Aeneas’s sword. Illuminata summarises this explicitly, still reflecting on the position of Dido dying on the pyre: “Like Dido, we ordinary women are merely tools in the tales of men. We can never be the protagonists of our own stories. No woman is exempt from that, from the empress to a nun. It is our lot.”

If the woman can only fulfil one role, as was mostly the case in 16th century Bavaria, this statement certainly holds true. But Illuminata’s position is unique, because the rhizomes created by hypermediation. This allows her to move in and out of different texts and role models based on her own choices and value judgements. This movement endows her with more agency than, for example, the way Andreas navigates the labyrinths (as spaces that are organised independently from the will of the one who walks them). This idea is also reflected in the second illustrated book, Andrea de Barberino’s knightly novel Il Guerrin Meschino, which Illuminata and Andreas mock with relish. Illuminata initially only speaks from the edge of the page -- clearly from the position of an outsider -- and then takes the form of a lady (also a spectator, not a participant) watching a joust. The third book reinforces the dilemmas women face in the limited roles available to them in this society. Marguerite Porete’s mystical work The Mirror of Simple Souls was persecuted along with its author as heretical by the Church in the early 14th century, and all copies of it were burned. The game does not clarify either the title or the author of the manuscript, but it is noteworthy that this is the first time in the game that we see a text-only manuscript page. In the previous illustrations, Sister Illuminata consistently occupied female positions: Dido or a lady spectator at the joust. Here, the initial lack of illustration may imply that the game uses the possibility of authorship to spectacularly expand the categories of female roles that were so limited by the late medieval and early Modern age. Moreover, the second illustrated page of Porete’s treatise does include an image with a female and a male figure ascending on two ladders towards God, promising the possibility of female transcendence.

The expansion of female roles is also confirmed by the closing image of the game: after Magdalene leaves, Andreas stays in Tassing, drawing with the village children under the windmill's rotating arms. The characters disappear, but the stick drawings remain. The frame freezes and then appears as an illustration of a realistically rendered three-dimensional manuscript page as the camera pans back (see Figure 6). This panning movement toward the player’s perspective further expands the rhizome towards the player’s reality. The Latin text below the illustration, written in scrawled letters, reads:

“Ante hodiem meum nomen meo operi signum dedi. (…) Soror Amalie Volklingenis” (On this day I sign my work with my name. (…) Sister Amalie of Volklingen).

Figure 6. Sister Amalie's name at the end of the manuscript. Click image to enlarge.

With this conclusion, Andreas and the others become mere characters in the story that is ultimately written and signed by the hitherto misled, exploited, voiceless Sister Amalie -- unlike the typically anonymous copyists of the Middle Ages, or even Andreas’s masterpiece that starts out as a copy itself. As the hypermediated rhizome guarantees a passage between different levels of diegesis, Sister Amalie gains authorial authority that derives from the non-hierarchical, decentralised, non-linear structure of the rhizome rather than the purposeful labyrinth-walking of the humanist subject.

Conclusion: Our Lady of the Rhizome

The word pentimento, from which the title Pentiment derives, implies a sense of layering, another image that emerges from underneath a surface layer. The image resonates metaphorically with the uncovering of non-hegemonic voices and narratives. Just as Pentiment relies on layers of superimposed, past readings, so too does the humanist subject and the emergence of the non-hegemonic voices that coexist with it. In the wake of technomedial changes, Pentiment demonstrates how the age of the printing press created a notion of time that could be precisely measured and dissected. The rational humanist subject emerged from this new mediated temporality, capable of triggering change and navigating his own labyrinth of choices. At the same time, behind the seemingly homogeneous and neatly shaped image of the Renaissance man’s quest for control, there is the multiplicity of his Others, often fragmented and incomplete, yet still capable of asserting agency and voicing their counter-histories.

I have argued that Pentiment stages this shift through both its narrative and game mechanics, in which the rhizome structure -- enabled by the game’s hypermediation of codex culture -- subverts the dominant subjectivity that it appears to simulate. Sister Amalie’s full signature reads “Soror Amalie Volklingenis, Nostra domina labirinthi”: Sister Amalie of Volklingen, Lady of the Labyrinth, where the sister reborn in the heart of the labyrinth takes on the attributes of the Virgin Mary. But this sanctified centre is not singular -- it is a node in a branching, recursive system established by the game’s narrative structure, its symbolism and the choices that the player is encouraged to make. The past that Sister Amalie embodies is neither static nor singular, but is rewritten through playful acts of remediation. Moreover, this past is already affected by the player’s decisions. In the ludic-textual mazes of the game, the player not only walks the labyrinth as an exercise in choice and agency, but also takes part in rewriting the labyrinthine text as a possibility space where tradition and dissent unfold together as a form of rhizomatic multivocality. We could therefore dub Sister Amalie Nostra domina rhizomatis -- Lady of the Rhizome.

References

Alvis, A. (2022, December 7). Pentiment: An Interview with Josh Sawyer -- SHARP NEWS. Sharpweb. Retrieved February 9, 2024, from https://sharpweb.org/sharpnews/2022/12/07/pentiment-an-interview-with-josh-sawyer/

Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural memory and early civilization: Writing, remembrance, and political imagination. Cambridge University Press.

Babka, A., Kernmayer, H., Lingl, J., & Schmutz, M. (2023). Introduction: Posthumanist Gender Theory -- A Very Rough Account. Genealogy+Critique, 9(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.16995/gc.10863

Bényei, T. (2000). Rejtélyes rend. A krimi, a metafizika és a posztmodern. Akadémiai Kiadó.

Bolter, J. D., & Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation: Understanding new media. MIT Press.

Borges, J. L. (1999). The Garden of Forking Paths. In Collected fictions (pp. 119-128). Penguin.Borges, J. L. (1999). The Library of Babel. In Collected fictions (pp. 112-118). Penguin.

Bostal, M. (2019). Medieval video games as reenactment of the past: a look at Kingdom Come: Deliverance and its historical claim. Del siglo XIX al XXI. Tendencias y debates: XIV Congreso de la Asociación de Historia Contemporánea, Universidad de Alicante 20-22 de septiembre de 2018, Mónica Moreno Seco (coord.) & Rafael Fernández Sirvent y Rosa Ana Gutiérrez Lloret (eds.) Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, pp. 380-394.

Braidotti, R. (2022). Posthuman Feminism (1st edition.). Polity.

Burdette, D. (2022, November 14). Pentiment review -- A clear picture. GAMINGTREND. Retrieved August 9, 2023, from https://gamingtrend.com/feature/reviews/pentiment-review-a-clear-picture/

Caracciolo, M. (2023). Remediating Video Games in Contemporary Fiction: Literary Form and Intermedial Transfer. Games and Culture, 18(5), 664-683. SAGE Publications.

Chapman, A. (2016). Digital Games as History: How Video Games Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. Routledge.

Cooper, V. (2019, March 28). Medievalism in Games: An Introduction. The Public Medievalist. Retrieved February 9, 2024, from https://publicmedievalist.com/intro-games/

Corbett, N. (2009). Digital Performance, Live Technology: Video Games and Remediation. Performing Adaptations: Essays and Conversations on the Theory and Practice of Adaptation, 11. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (B. Massumi, Tran.) (First Edition.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Doob, P. R. (2019). The idea of the labyrinth from classical antiquity through the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press.

Eco, U. (1980). The Name Of The Rose (Reprint edition.). HarperVia.

Eco, U. (1995). Faith in fakes: Travels in hyperreality. Random House.

Eisenstein, E. L. (1980). The printing press as an agent of change (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Eliade, M. (1957). Mythes, reves, et mysteres. Gallimard.

Faris, W. B. (1988). Labyrinths of Language: Symbolic Landscape and Narrative Design in Modern Fiction. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fernández-Vara, C. (2018). Game Narrative Through the Detective Lens. Proceedings of Digra 2018.

Ferrando, F. (2019). Philosophical Posthumanism. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Girina, I. (2013). Video game Mise-En-Scene remediation of cinematic codes in video games (pp. 45-54). Presented at the Interactive Storytelling: 6th International Conference, ICIDS 2013, Istanbul, Turkey, November 6-9, 2013, Proceedings 6, Springer.

Grossman, L., Billips, M., & Schultz, M. (2002). Feeding on Fantasy. Time, 160(23), 90-92. Time Incorporated.

Hafer, L. (2022, November 14). Pentiment Review. IGN. Retrieved August 13, 2023, from https://www.ign.com/articles/pentiment-review

Haig, M. (2020). The Midnight Library: The No. 1 Sunday Times bestseller and worldwide phenomenon. Canongate Books.

Houghton, R. (2024). A Violent Medium for a Violent Era: Brutal Medievalist Combat in Dragon Age: Origins and Kingdom Come: Deliverance. Studies in Medievalism, XXXIII, 119-143.

Ivănescu, A. (2019). Games on Media: Beyond Remediation. In A. Ivănescu (Ed.), Popular Music in the Nostalgia Video Game: The Way It Never Sounded, Palgrave Studies in Audio-Visual Culture (pp. 29-74). Cham: Springer International Publishing. Retrieved January 26, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04281-3_2

Kirkland, E. (2009). Resident Evil’s Typewriter: Survival Horror and Its Remediations. Games and Culture, 4(2), 115-126. SAGE Publications.

Kittler, F. A. (2001). Perspective and the Book. (S. Ogger, Tran.)Grey Room, (5), 39-53. JSTOR.

Kleinerman, D., & Haynes, C. (2023, June). Regret in Play and in Paint: Authorship, Narrative, and Intertextuality in Pentiment (2022). In Abstract Proceedings of DiGRA 2023 Conference: Limits and Margins of Games.

McLuhan, M. (2003). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Critical Edition). Gingko Press.

Obsidian Entertainment. (2022). Pentiment [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Josh Sawyer and published by Xbox Game Studios.

Warhorse Studios. (2018). Kingdom Come: Deliverance [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Game Silver.

Perron, B., Montembeault, H., Morin-Simard, A., & Therrien, C. (2019). The Discourse Community’s Cut: Video Games and the Notion of Montage. Intermedia Games -- Games Inter Media (pp. 37-68).

San Nicolás Romera, C., Nicolás Ojeda, M. Á., & Ros Velasco, J. (2018). Video Games Set in the Middle Ages: Time Spans, Plots, and Genres. Games and Culture, 13(5), 521-542. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

Sawday, J., & Rhodes, N. (2002). The Renaissance Computer: Knowledge Technology in the First Age of Print. Routledge.

Schild, J. (2023, January 9). The Talking Scripts of Obsidian’s Pentiment. Language at Play. Retrieved August 13, 2023, from https://languageatplay.de/2023/01/09/the-talking-scripts-of-obsidians-pentiment/

Vandewalle, A. (2023). Video Games as Mythology Museums? Mythographical Story Collections in Games. International Journal of the Classical Tradition, 1-23. Springer.

Watts, R. (2022, November 15). Pentiment review: A captivating murder mystery spanning 25 years of rich medieval history. Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved August 13, 2023, from https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/pentiment-review

Yaza Games. (2022). Inkulinati. [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Wojtek Janas and published by Daedalic Entertainment.

Wright, E. (2024). “Layers of History”: History as Construction/Constructing History in Pentiment. ROMchip, 6(1), Article 1. https://romchip.org/index.php/romchip-journal/article/view/191