Paratextuality in Game Studies: A Theoretical Review and Citation Analysis

by Jan ŠvelchAbstract

Paratext is a frequently used concept in game studies, mentioned approximately 300 times in the 2010s alone. However, it is not Gérard Genette’s original definition from 1982, but rather the expanded version proposed by Mia Consalvo in 2007 that is used in 70 percent of the 235 analyzed academic texts written in English and published between 1997 and 2019. This article provides a critical theoretical review of current paratextual scholarship and uses citation analysis to quantify the existence and impact of three different approaches to paratext: original, expanded, and reduced. In particular, the expanded framework, which is, according to the analysis, usually attributed to Consalvo, tends to be too all-encompassing by stripping away the original limitation on authorship of paratextual elements and instead resembles the screen studies term cultural epiphenomena. In the article, I highlight the differences between the three frameworks and track the frequency of their use in game studies scholarship. Additionally, I propose a methodological intervention by suggesting to avoid the reductive term “paratext” in the sense of a category of texts, which implies a rigid textual hierarchy. Instead I recommend treating paratextuality as a link between a text and the surrounding socio-historical reality, emphasizing that paratextuality is often accompanied by other (trans)textual qualities.

Keywords: paratext, paratextuality, transtextuality, intertextuality, cultural epiphenomena, literary theory, citation analysis

Introduction

Over its 38 years long history, the concept of paratext has been adopted by many fields and applied to various phenomena across different cultural and media industries. It has also been widely used in game studies -- but often in ways that have departed from the original framework as conceived by Gérard Genette in 1982, as others have noted before (Arsenault, 2017; Backe, 2017; Rockenberger, 2014; Švelch, 2016, 2017b). This process of appropriation and redefinition is logical due to the underlying bias of Genette’s conceptualization of paratext towards the codex book medium -- specifically related to commercial book publishing between 18th and 20th century (cf. Bredehoft, 2014; Jansen, 2014; Smith & Wilson, 2011). An unorthodox use of terminology can nevertheless lead to general confusion, misinterpretation, and misattribution of new versions of the concept to scholars who envisioned it differently, leading some scholars to question the concept’s analytical value (e.g. Guins, 2014). As a field that has been widely using paratextuality since 2011, game studies can therefore benefit from a critical meta-review of the existing frameworks and a methodological intervention. The goal of this article is to address the theoretical foundations of the concept, highlight the differences among its three main frameworks (original, expanded, and reduced), and track their use in game studies publications. The theoretical part of this article draws partly from my doctoral thesis (Švelch, 2017b), but presents a streamlined and updated review of the three aforementioned frameworks. The quantitative citation analysis is an original contribution, which is inspired by Fredrik Åström’s (2014) general bibliometric study of paratext and Genette’s other texts, but provides a more focused exploration of a singular scholarly field.

While the main focus of this article lies in the field of game studies, the often emphasized interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary nature of game studies (Aarseth, 2001; Martin, 2018; Mäyrä, 2009; Quandt et al., 2015) necessarily broadens the scope of the presented discussion about paratextuality. As such, I also consider relevant contributions from screen studies, media studies, and literary theory.

The Value of Paratextual Inquiry

Genette (1997a [1982]) coined the term paratext to draw attention to overlooked elements of book publishing, such as the title, preface, or notes. By focusing on these seemingly ancillary parts of a literary text, he highlighted their role as important framing devices and, to a certain extent, also questioned the centrality of a text. In this sense, paratextuality connects to Roland Barthes’ (1987) titular proclamation in The Death of the Author by admitting that authorial vision is not automatic or omnipotent and instead requires paratextual elements for enforcing the preferred meanings. While this line of thinking suggests that the meaning and interpretations of a text can be adjusted or influenced by paratextual elements, Genette still considered them to be (in an ideal scenario) subordinate to the main text (and its author or publisher). In Genette’s view, literary scholarship should acknowledge the importance of paratextual phenomena but the hierarchy of individual elements of codex book publishing remains largely the same, with the main text at the top regarding its cultural status.

The idea of decentralization of cultural industries in terms of their dominant cultural form was further discussed by Peter Lunenfeld in the context of new media. In contrast to Genette, Lunenfeld argued that paratextual elements were becoming more popular and noteworthy than what was traditionally considered the main text:

[…] the backstory--the information about how a narrative object comes into being--is fast becoming almost as important as that object itself. For a vast percentage of new media titles, backstories are probably more interesting, in fact, than the narratives themselves. (Lunenfeld, 1999, p. 14)

This argument was later picked up by game scholars Mia Consalvo and Steven E. Jones, who both advocated for a more equal treatment of paratextual elements compared to games themselves. For Consalvo (2007), one of the main reasons for the importance of paratextuality was its value for acquiring gaming capital (e.g. by reading walkthroughs or strategy guides players can gain a higher status within a community), a variation on Bourdieu’s cultural capital (see also Consalvo, 2019). Jones argued that popular games: “[are] predominantly paratextual. That is, the formerly limited role of the paratext, to serve as a threshold or transactional space between the text and the world, has now moved to the foreground, has become the essence of the text.” (S. E. Jones, 2008, p. 43) Here, Jones moves away from Genette’s original framework by suggesting that the mere quantity of paratextual elements subverts the primacy of the main text. This shift goes hand in hand with Consalvo’s and Jones’ interest in the audience perspective rather than the side of production, which had played a more central role in Genette’s (1997b [1987]) own discussion of paratextuality. More recently, Consalvo (2017) has argued that games themselves become paratextual in the context of other popular phenomena of video game culture, such as mods and streaming.

[…] games themselves become paratexts--supporting texts--to other more central media artifacts. Removing or de-centering games from what we might think of as their more central position in a game studies analysis demonstrates their contingent nature in the realm of meaning making--and the contingent placement of any such text. (Consalvo, 2017, p. 182)

Despite the shifts in its usage, paratextuality still retains some of its original analytical value in exposing the complexities of cultural industries. As Jonathan Gray has argued, it is not only the triangle of producers, texts, and audiences that requires scholarly attention but also the links and spaces between these elements, which are to a large degree enabled by paratextual phenomena.

If we imagine the triumvirate of Text, Audience, and Industry as the Big Three of media practice, then paratexts fill the space between them, conditioning passages and trajectories that criss-cross the mediascape, and variously negotiating or determining interactions among the three. (Gray, 2010, p. 23)

Paratextuality as a concept is thus valuable for various strands of game studies scholarship, including production studies, player and reception studies, but also for formal analysis and close reading as it tackles issues such as structural relationships between game-related phenomena, framing effects, promotion (Johnston, 2013) and technical communication (deWinter & Moeller, 2014; Eyman, 2008; Mason, 2013), and reception (see also Švelch, 2016, 2017b). It has also been used in current debates about increasingly popular forms of game culture, such as streaming and esports (e.g. Consalvo, 2017; Egliston, 2019; Spilker et al., 2020).

The Multiple Frameworks of Paratextuality

Even though the concept of paratextuality is often considered a separate entity and it is often presented as such in recent publications (see Stanitzek, 2005 [2004]), it was originally introduced as a part of a larger typology of transtextuality, also known as textual transcendence (Genette, 1997a [1982]). Its aim was to provide a more nuanced vocabulary to tackle various relationships between texts, cultural practices, and socio-historical circumstances of literary texts than the very broad concept of intertextuality (Kristeva, 1969). In this typology, paratextuality was one of five aspects of transtextuality along with a limited version of intertextuality (co-presence of one text in another), metatextuality (critical commentary of a text), hypertextuality (transformation of a text, e.g. adaptation or parody), and architextuality (a text’s relation to a genre or literary practice).

Genette was not entirely clear how his typology applies to literary genres and practices. On the one hand, he emphasized that these five qualities of texts are not mutually exclusive and often appear together: “one must not view the five types of transtextuality as separate and absolute categories without any reciprocal contact or overlapping. On the contrary, their relationships to one another are numerous and often crucial.” (Genette, 1997a, p. 7 [1982]) On the other hand, Genette suggested that they establish particular categories of texts.

[…] every text may be cited and thus become a quotation, but citation is a specific literary practice that quite obviously transcends each one of its performances and has its own general characteristics; any utterance may be assigned a paratextual function, but a preface [paratext] is a genre […]; criticism (metatext) is obviously a genre […] (Genette, 1997a, p. 8 [1982])

This step from a typology of textual qualities (transtextuality) to a typology of texts (transtexts) is problematic as it threatens to oversimplify the complex nature of texts (Švelch, 2016, 2017b). Genette himself admitted that:

If one views transtextuality in general not as a classification of texts (a notion that makes no sense, since there are no texts without textual transcendence) but rather as an aspect of textuality, […] then one should also consider its diverse components (intertextuality, paratextuality, etc.) not as categories of texts but rather as aspects of textuality. (Genette, 1997a, p. 8 [1982])

In practice, labeling a certain artifact as a paratextual element should not mean that other aspects of transtextuality are not co-present. For example, Easter eggs can be paratextual if they include information such as the name of a game’s author, as was the case of Warren Robinett’s hidden message in the game Adventure (Atari, 1979; see Consalvo, 2007; Montfort & Bogost, 2009; Nooney, 2014; Whalen, 2012). In other cases, Easter eggs might become intertextual if they contain references to other games. Thus, rigidly classifying certain genres or types of cultural phenomena as “paratexts” (or as any other “transtexts”) might obscure their various co-existing qualities by relegating them to one very narrow role.

The Original Definition

Genette’s paratextuality has distinct defining features compared to the other types of transtextuality. It serves as a figurative threshold of a text by grounding it in the surrounding socio-historical reality. This grounding can be performed by elements ranging from titles and colophons to authorial prefaces or even the materiality of the cultural artifact as such (e.g. the physical medium of a book, its size, or typography). According to Genette, “paratexts” as a category of texts can then be understood as elements with a paratextual function. The etymology of the word should not suggest that paratextual elements need to be necessarily textual (i.e. verbal). Genette himself identified at least three other possible types of substantiality: “iconic” (e.g. illustrations), “material” (e.g. typography), and “factual” (possibly any contextual information; discussed in more detail in the section about the reduced definition) (Genette, 1997b, p. 7 [1987]). In this sense, paratextual elements are not bound to any specific form, verbal, physical, or otherwise.

In contrast to this breadth of possible paratextual forms, Genette is strict about the issue of authorship: “By definition, something is not a paratext unless the author or one of his associates accepts responsibility for it, although the degree of responsibility may vary.” (Genette, 1997b, p. 9 [1987]) This part of Genette’s definition has been overlooked by many of the more recent interpretations (e.g. Aarseth, 1997; Consalvo, 2007, 2017; Gray, 2010; S. E. Jones, 2008) despite playing a major role in distinguishing between paratextual and metatextual phenomena (see also Arsenault, 2017; Rockenberger, 2014; Švelch, 2016, 2017b). The former is limited only to elements created or commissioned by the original production collectives whose members cannot plausibly claim a critical distance from a cultural artifact that they refer to. The latter category of metatextuality highlights the ideally independent position of external commentary, which by default does not create any conflict of interests between the commentators and the producers of the text.

Partly due to their official authorship, Genette (Genette, 1997b [1987]) argues that paratextual elements are subordinate and that they should not attract too much attention to themselves at the expense of the main text. While this might be true for certain elements, such as credits or prefaces, this notion of subordination explicitly dismisses the cultural importance of paratextual elements as a whole (cf. Brookey & Gray, 2017; Consalvo, 2017; Gray, 2010; S. E. Jones, 2008; Lunenfeld, 1999; Rockenberger, 2014; W. Wolf, 2006). On an empirical level, trailers have become a prime counterexample to this problematic assumption of subordination. Besides informing about a different cultural artifact, trailers to many viewers offer a self-contained aesthetic and entertainment value (Hesford, 2013; Johnston et al., 2016; Švelch, 2017a; Vollans, 2015, 2017).

Throughout Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, Genette (1997b) creates elaborate classifications and typologies of paratexts. I have already covered the crucial aspects of substantiality and authorship in the previous paragraphs. Many other aspects (e.g. temporality, addressee, the sender’s degree of authority) do not have direct impact on the underlying definition of paratextuality; instead they exemplify practical aspects of literary publishing and provide a more detailed analytical toolset. This also applies to the spatial dimension of paratexts, which has become one of the most discussed and criticized features of Genette’s framework (see Dunne, 2016; S. E. Jones, 2008; Lunenfeld, 1999; McCracken, 2012; Stewart, 2010; W. Wolf, 2006). The binary of peritexts (paratextual elements spatially connected to a cultural artifact) and epitexts (spatially removed) is based on the codex book medium and hardly fits other cultural artifacts. However, this distinction is not a central part of the definition, as the sum of these two categories allows for any spatial relation between an artifact and its paratextual element.

The Expanded Definition

Since the historically first mention of paratext in game studies (Aarseth, 1997), game scholars have broadened Genette’s concept to accommodate for elements created by other parties than game producers and their associates. Early on, the term paratext was used to refer to game magazines, player comments, or unofficial walkthroughs (Aarseth, 1997; Consalvo, 2007). Within Genette’s framework of textual transcendence, these phenomena would instead fall under metatextuality due to their external origins and commentary-like character. Additionally, the expanded definition also treats various hypertextual artifacts as primarily paratextual, including for example alternate reality games, tie-in novels, or web series (S. E. Jones, 2008). While many of these artifacts indeed ground concrete games in a socio-historical reality, they either do not fulfil the original limitation on authorship or are highly self-sufficient as texts in their own right and therefore would rather qualify as hypertextual objects, similarly to adaptations or sequels.

The expanded version of paratextuality closely resembles the term “cultural epiphenomena” (Heath, 1976; Klinger, 1989). This negatively defined concept was coined in screen studies to tackle all film- and television-related phenomena that are not film and television per se but are somehow connected to them, such as fan letters, posters, reviews, recaps, or trailers. Coincidentally, screen studies now also often uses the broader definition of paratextuality due to the widely cited book by Jonathan Gray Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (2010), which re-introduced Genette’s concept to the field.

The Reduced Definition

Taking an opposite stance towards the original definition, Werner Wolf (2006) proposed a more limited version of paratextuality in the context of literary theory and media studies. This framework was later applied to game studies by David Jara (2013) and Annika Rockenberger (2014). Although this approach inhabits a small niche in game scholarship, it is a relevant contribution to the overall discussion about paratextuality due to its rigorous conceptualization. One of the main criticisms raised by Wolf and his followers is the breadth of Genette’s original definition, especially when it comes to the factual paratext. Genette writes that: “By factual I mean the paratext that consists not of an explicit message (verbal or other) but of a fact whose existence alone, if known to the public, provides some commentary on the text and influences how the text is received.” (Genette, 1997b, p. 7 [1987]) In order to limit any contextual information from becoming a de facto paratextual element, Wolf effectively reduced Genette’s concept to its original subcategory of verbal peritext (i.e. spatially connected verbal paratextual element). In Wolf’s version of paratextuality, only phenomena like introductory sequences or menus can be considered paratextual elements, while various promotional materials located outside of the game were redefined as other types of framings.

|

Framework |

Conceptualization |

Examples of Game-Related Paratextual Phenomena |

|

Original |

Elements that form a figurative threshold of a text and ground it in a socio-historical context. Ideally, they are subordinate to the text. They must be created by the text’s producers or their associates. |

Promotional materials, introductory sequences, menus, credits, making-ofs, contextual information about authors. |

|

Expanded |

Any element that forms a figurative threshold of a text and grounds it in a socio-historical context. There are no limitations on authorship or cultural status of a paratextual element. |

All the phenomena from the original framework + criticism and journalism, user discussions, fan fiction and fan art, streaming, transmedia storytelling. |

|

Reduced |

Primarily verbal and spatially connected (peritextual) elements that form a figurative threshold of a text and ground it in a socio-historical context. They are usually subordinate but can also be self-centered. They are created by the text’s producers or their associates. |

Introductory sequences, menus, in-game credits. |

Trajectory of Adoption

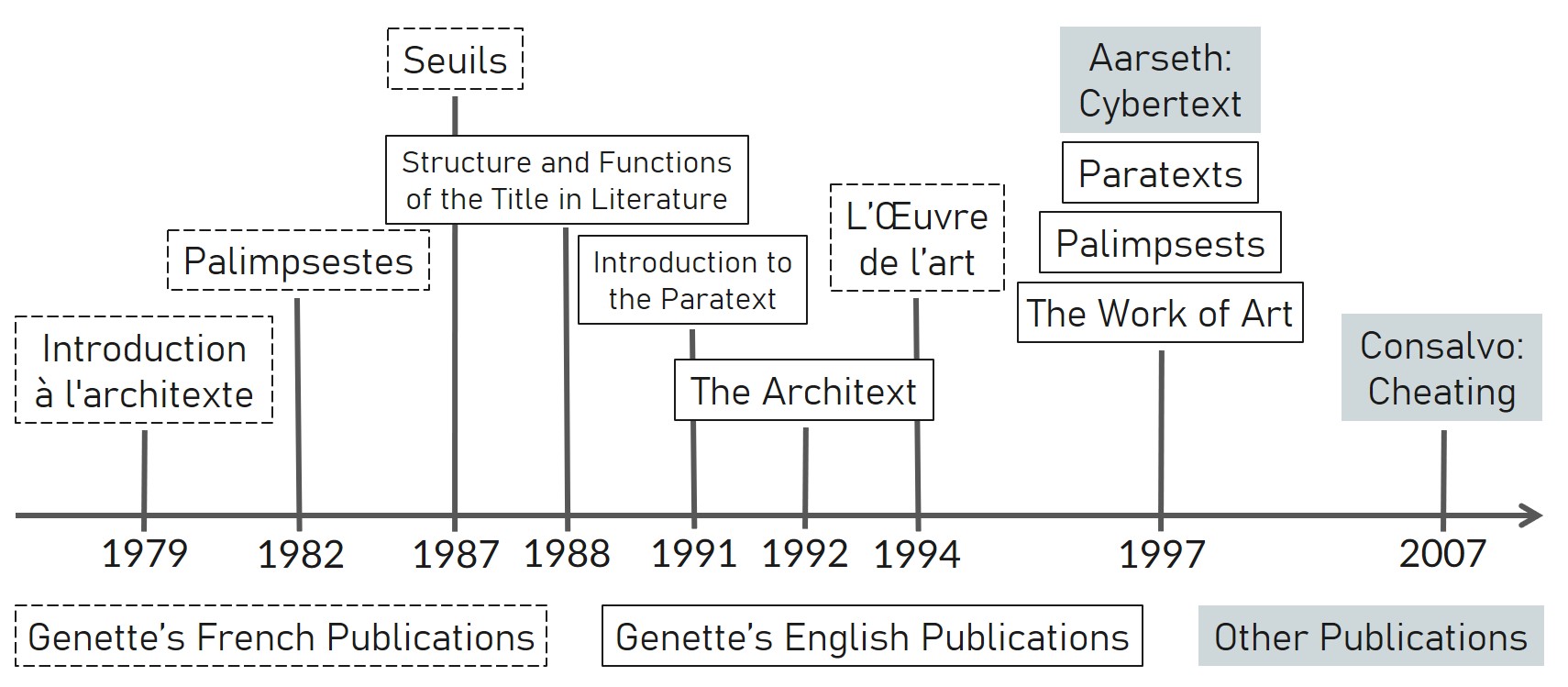

The way paratextuality became accessible to different parts of academia can shed light on its reception and interpretation, especially since Genette’s books that deal with the paratextual framework had been originally published in French and only later translated into English. Curiously, the first mention of paratextuality in the original French edition of Introduction à l'architexte (Genette, 1979) had a different meaning and was later renamed to hypertextuality in Palimpsestes: La littérature au second degré (Genette, 1982). Palimpsestes is the only place where Genette himself in detail elaborates on the theoretical foundations of transtextuality and on the interplay between its specific types (Genette, 1997a, pp. 1-9 [1982]). However, most of the monograph is dedicated to hypertextuality (in its amended meaning). The most central publication for paratextuality is Seuils (Genette, 1987), which engages in empirical analysis of various paratextual elements in book publishing [1]. Later, Genette also used the concept of paratext in L’Oeuvre de l’art: Immanence et transcendance (Genette, 1994), which broadened up his area of interest from literature to other works of art.

Genette’s texts related to paratextuality started first appearing in English as translations of individual chapters from Seuils -- “Structure and Functions of the Title in Literature” (Genette, 1988) and “Introduction to the Paratext” (Genette, 1991) [2]. These were followed by The Architext: An Introduction (Genette, 1992 [1979]) with the then already outdated version of the concept (as hypertextuality). In 1997, the two central books were published in English and accompanied by new forewords (Genette, 1997a [1982], 1997b [1987]). Gerald Prince’s (1997) brief foreword to Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (Genette, 1997a [1982]) emphasized the connection between Genette’s three books on textual transcendence (Genette, 1979, 1982, 1987) and implied that they should be considered as a part of a series. Richard Macksey’s (1997) more sizeable foreword to Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (Genette, 1997b [1987]) essentially summarized the typology of transtextuality as explained in Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree, including the difference in authorship between paratextuality and metatextuality. More importantly, it addressed the fact that Genette assumed throughout the book that readers had already been familiar with his typology and therefore did not spend any time re-introducing it. However, in the context of English-speaking academia the two books in question came out in the same year. Their relation could then be perceived as parallel instead of serial [3]. Coincidentally, the relatively newer L'Oeuvre de l’art: Immanence et transcendance (Genette, 1994) was translated to English also in 1997 (Genette, 1997c).

The first appearance of the term paratext in game studies can be traced to Espen Aarseth’s Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (1997), usually considered one of the canonical works of game studies. Aarseth mentioned the concept only on one page, used it primarily to talk about the so-called walkthroughs, and did not reference Genette explicitly.

[…] paratexts [are], accompanying texts that refer to the game in some way, like the reviews of a theater play or its program brochure. The paratexts are of course not limited to the official Infocom [a video game company] package but may include comments and solutions made by players for each other. A common unofficial paratext is the “walkthru”, a step-by-step recipe that contains the solution, and “walks” the user through the game. (Aarseth, 1997, p. 117)

This first use of Genette’s concept in the context of games already marked a departure from the original meaning towards the expanded definition by including third-party texts -- reviews or player-made walkthroughs. Despite being present in Aarseth’s monograph, which has gathered over 5,100 Google Scholar citations by May 2020, paratextuality has not become part of game studies’ analytical inventory until after its appearance in Consalvo’s Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames (2007). Consalvo dedicated more space to the introduction of the concept, including an explicit attribution to Genette, and used paratext throughout her whole book. However, her use of the term much more resembles Aarseth’s earlier interpretation rather than Genette’s original definition. Consalvo even coined her own related term “paratextual industry” (Consalvo, 2007, p. 4) in order to talk about ancillary video game-related business practices, such as the specialized press, game guide publishing, or mod chip manufacturers. The adoption of paratextuality was further solidified by Steven E. Jones’ The Meaning of Video Games: Gaming and Textual Strategies (2008), in which he used this concept to analyze tie-in novels, alternate reality games, and web series. All three aforementioned uses of paratext in game studies followed the expanded definition [4].

Methodology

To map the current state of paratextual scholarship in game studies, I created a corpus of publications published between 1997 and 2019 in English that use Genette’s concept. The collection process was laborious as there is no dedicated database for game studies and many of its journals (e.g. Analog Game Studies, Loading…, Kinephanos, Press Start, or Well Played) are not properly indexed in databases such as Scopus or Web of Science. Limiting the scope of the study to these established databases would make the collection process arguably more objective and easier to reproduce, but would not do justice to the richness of scholarly discussions about game studies and paratextuality by focusing only on a subset of publications, leaving out the aforementioned journals, and also many books and chapters from edited collections. My aim was to cover a wide range of game studies texts without structurally prioritizing indexed journal articles. To achieve this, I had to search many venues manually, while also following citations in the already discovered publications to gather additional items for the corpus. This way I was able to include even relatively alternative journals like Analog Game Studies or the student-led Press Start, which both prefer editorial curation and open review process over more standard mutually anonymized peer review. Books and book chapters posed the greatest difficulties for data collection due to their limited accessibility. While it is possible that some were omitted in the final corpus, I have made a deliberate effort to collect as many as I could find. The manual search was then complemented by multiple rounds of Google Scholar search queries using the phrase “games? + paratext?” before the submission of the article at the end of 2018 and during the revision process in the second quarter of 2020.

For the corpus, I considered only books, book chapters, conference full papers, and journal articles dealing with games as one of their main topics [5]. Other genres such as book reviews, conference abstracts, special issue introductions, interviews, and dissertation theses were left out. Beside this general criterion, all considered publications had to elaborate on their chosen approach to paratextuality, including operationalization of at least one concrete phenomenon as a paratextual element (e.g. cover, Let’s Play, manual, review, user interface). Brief mentions of the term without any further explanation were discarded as it would have been impossible to distinguish which version of paratextuality they employed. During this step, more than 100 publications were excluded from the corpus. The final count of 235 items consists of 24 books, 51 book chapters, 21 conference papers, and 139 journal articles (the full list is included as Appendix 1) [6].

The analysis of the corpus combined two approaches: (1) a manually coded citation analysis of key paratextual references a (2) descriptive overview of paratextual phenomena as operationalized by individual authors. The former used the method of frequency content analysis, which due to its objective criteria (presence or absence of a key reference) and triviality of the coding process did not require multiple coders and measuring of intercoder reliability (Krippendorff, 2004). The list of the following seven key references was constructed based on the theoretical contribution of these publications to the discussion about paratextuality in game studies and adjacent fields.

- Genette, G. (1997a [1982]). Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (C. Newman & C. Doubinsky, Trans.). University of Nebraska Press.

- Genette, G. (1997b [1987]). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (J. A. Lewin, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

- Consalvo, M. (2007). Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. MIT Press.

- Jones, S. E. (2008). The Meaning of Video Games: Gaming and Textual Strategies. Routledge.

- Gray, J. (2010). Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York University Press.

- Wolf, W. (2006). Introduction: Frames, Framings, and Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media. In W. Bernhart & W. Wolf (Eds.), Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media (pp. 1-40). Rodopi.

- Rockenberger, A. (2014). Video Game Framings. In N. Desrochers & D. Apollon (Eds.), Examining Paratextual Theory and its Applications in Digital Culture (pp. 252-286). IGI Global.

First, the list includes Genette’s two main texts related to paratextuality (Genette, 1997a [1982], 1997b [1987]). As mentioned, Palimpsests is a relevant resource for the original framework of paratextuality because it explains this concept within its original context of transtextuality even though much of this book focuses on hypertextuality. The assumption behind the inclusion of this text was that authors who are familiar with other types of transtextuality might be more likely to use the original (or possibly the reduced) definition to avoid conflating paratextuality with metatextuality. Besides these two references, I also looked for any full text mentions of Genette to account for any general acknowledgements of his authorship of the framework without a formal citation of his two key texts. This additional step also accounts for the cases in which authors cite some of the chapter excerpts (Genette, 1988, 1991) from Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, which had been published as separate articles before the entire monograph was translated into English.

Second, Consalvo’s (2007), Jones’ (2008), and Gray’s (2010) books are key sources for the expanded framework. The inclusion of these well-cited publications aims to determine which of them have been influential for game studies. Third, Wolf’s (2006) introductory chapter in the edited collection Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media (W. Wolf & Bernhart, 2006) and Rockenberger’s (2014) application of this approach to game studies represent the reduced framework. The latter text was included despite its relatively recent publication date because it explicates the connection between Wolf’s version of paratextuality and game-related phenomena.

The second part of the analysis was based on the manual reading of all 235 publications, searching for the words “paratext”, “paratextual”, and “paratextuality”, and identifying phenomena considered by respective authors of those publications to be “paratexts” or paratextual elements. The goal of this process was to determine which one of the two main frameworks -- original or expanded, respectively -- was used. I deliberately left out the reduced definition from this part of the analysis as it significantly overlaps with the original definition and has low citation numbers for its two selected publications, as I show in the next section. Overall, I deem this approach based on concrete operationalization of paratextuality more informative and accurate than identifying the chosen definition based on publication’s key references or authors’ own claims. Due to the strict differences between the two definitions, it was relatively easy to identify the chosen framework for each publication.

Citation Metrics

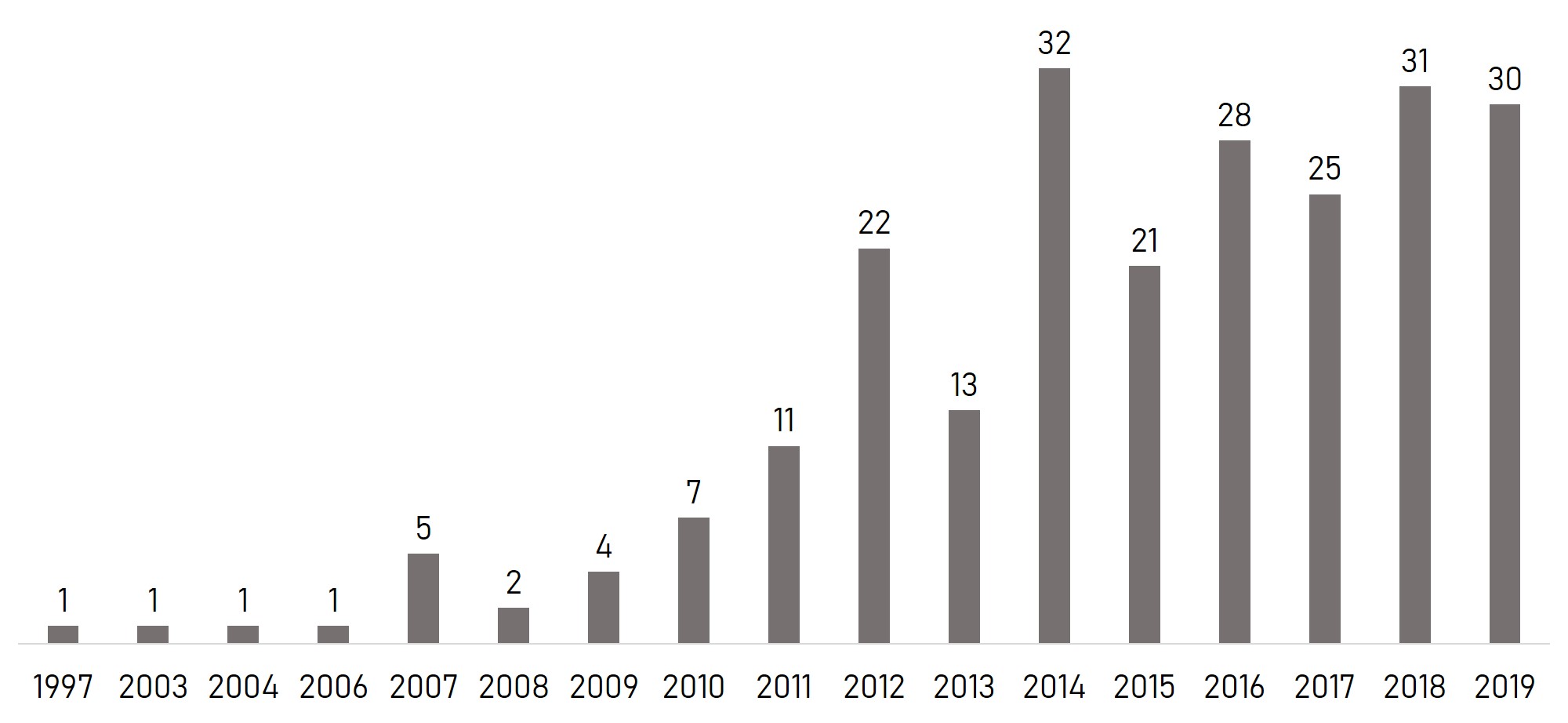

As previously mentioned, the term paratext appeared in game studies for the first time in 1997. However, in the following years, its use (as an analytical concept, not just as a brief mention) was rather sporadic. Even Consalvo’s more substantial discussion of the term from 2007 did not immediately increase the popularity of paratext. Figure 2 shows a more consistent rising trend of adoption beginning in 2010 and fully materializing in 2012. In fact, a vast majority of the collected academic texts (more than 85 percent) were published after 2012. The rise in the use of paratextuality coincided with the turn away from formalism in game studies (e.g. Consalvo, 2009; Juul, 2010; Sicart, 2011; T. L. Taylor, 2009; cf. Myers, 2010). Arguably, Genette’s concept can be applied both to formal analysis and more culture-oriented research, effectively bridging the two paradigms, but being especially relevant for studies that investigate the context of games. However, the increase does not necessarily mean a proportionately higher use of the concept in the whole body of game studies publications but can be also caused by the general growth of the field, including foundation of new journals and higher publication frequency of the existing ones. Nonetheless, the volume of paratext-related scholarship has relatively stabilized around 2014. Currently, it can be assumed that paratext has already established a strong position in game studies scholarship and will continue to appear in future publications. Paratextual scholarship about games was published in a wide range of journals (65) and conferences (15), including game studies-specific venues such as Games and Culture (19), Game Studies (8), or Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds (6) and more broadly oriented outlets like Kinephanos (8) or New Media & Society (7), to name the most frequent in these two categories.

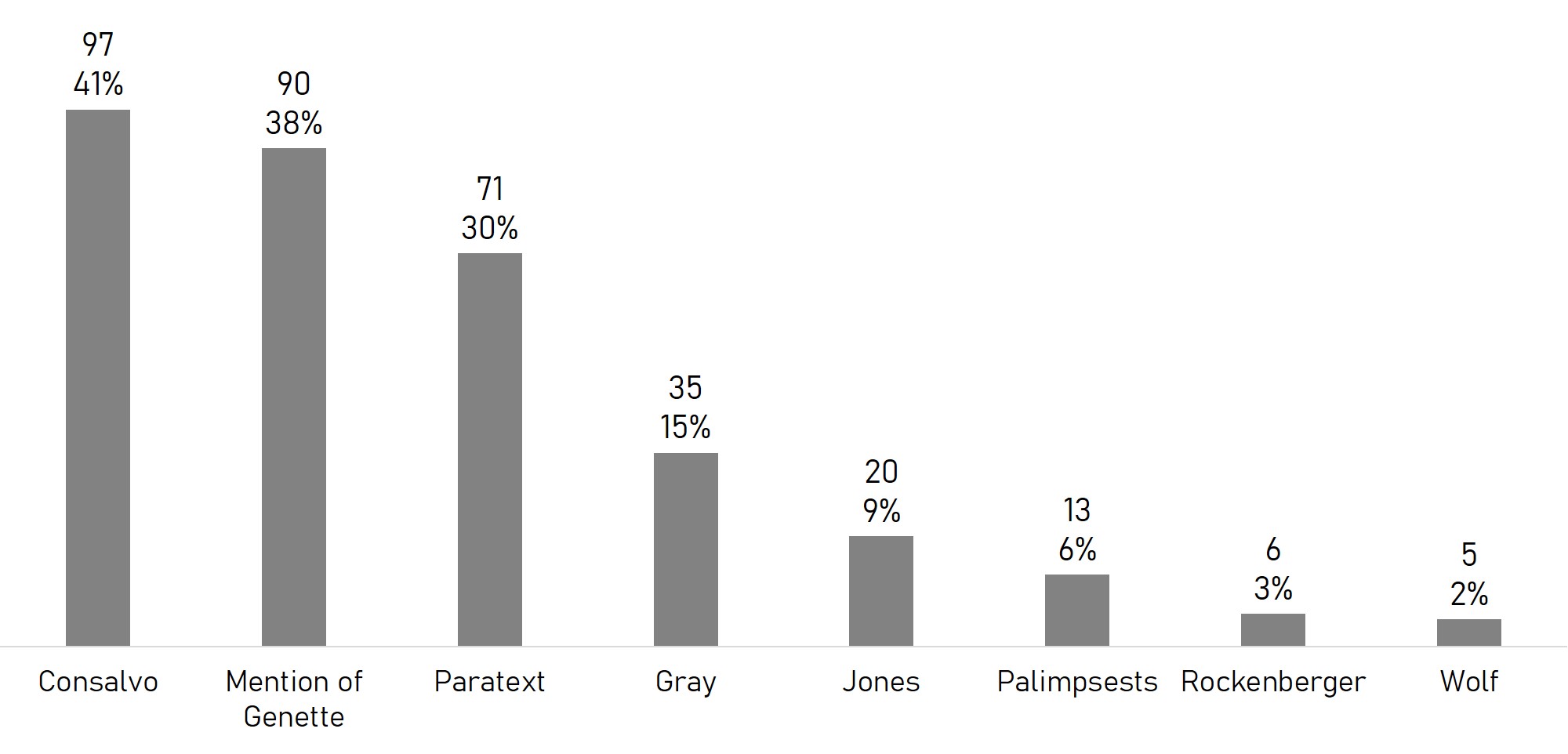

Figure 3 shows a relatively low percentage of texts (38 percent) that cited Genette when using the concept of paratextuality. This finding corresponds with results of Åström’s (2014) citation analysis of Web of Science texts about paratexts, which showed that out of 234 articles that mentioned “paratext” in the title, abstract, or among keywords, only 112 (roughly 48 percent) referenced Genette or his texts. Perhaps surprisingly, Consalvo’s Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames was more often cited than Genette’s Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (41 percent to 30 percent). Nonetheless, Consalvo and Genette occupied a similarly strong position as authorities on paratextuality in game studies, at least regarding their explicit acknowledgements in the analyzed texts. Roughly a half (46 out of 97 and 90, respectively) of Consalvo’s citations and Genette’s mentions appeared together, further suggesting that Consalvo popularized the term in game studies. Other key references appeared less frequently, especially the publications related to the reduced framework (Rockenberger, 2014; W. Wolf, 2006) were nearly absent from the corpus.

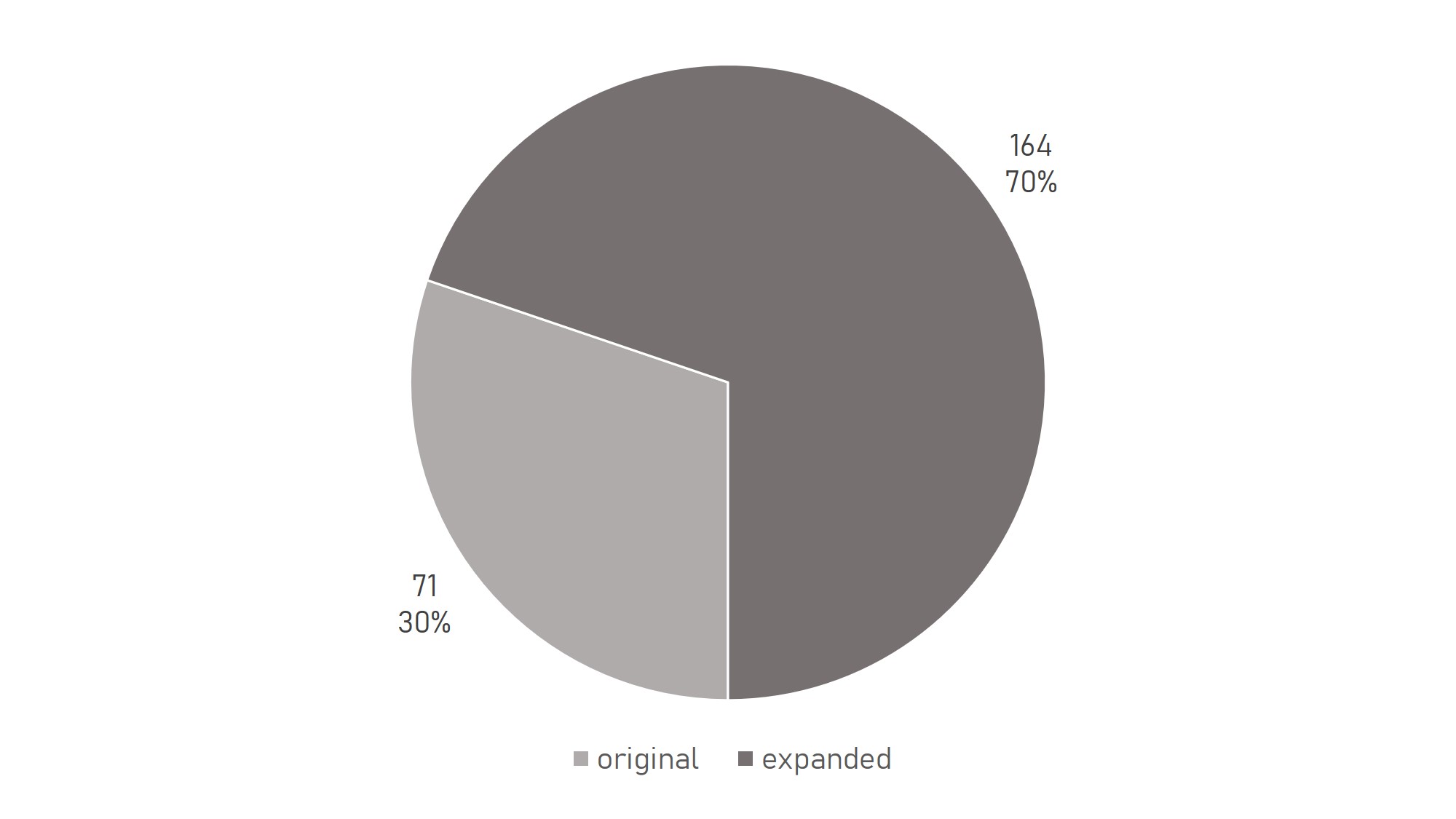

Consalvo’s high citation numbers partly explain the prevalence (70 percent) of the expanded framework within the corpus, as shown in Figure 4. A sizeable portion of these texts, however, acknowledged Genette and his work on paratextuality while applying the broader definition (roughly 36 percent out of the 164 texts that used the extended framework). This is an important piece of empirical evidence about the adoption of Genette’s concept. The departure from the original definition has been occasionally noted (Arsenault, 2017; Backe, 2017; Rockenberger, 2014; Švelch, 2016, 2017b), but until now its extent could have been only hypothesized. The presented data conclusively show that the redefinition, most visibly attributed to Consalvo, has already overtaken the original concept in game studies. While already the first publication (Aarseth, 1997) used the expanded definition, a more significant shift in this direction began in 2009. Until then the two frameworks had been more or less equally represented with five and six publications, respectively. Since 2011, the expanded definition has sustained a clear majority of two-thirds or more (from as much as 82 percent in 2011 to 67 percent in 2019) on an annual basis.

One possible explanation for the popularity of the expanded definition is the presentation of paratextuality in Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, which, in the main text, omits any reflection of the original theoretical foundations of the concept (transtextuality). This can lead to the assumption that any element that functions as the figurative threshold of a text is paratextual regardless of its authorship, thus conflating paratextuality and metatextuality into one broader term. As mentioned, Genette himself only discussed transtextuality in Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree, which was referenced only in six percent of all the analyzed academic texts. Out of these 13 publications, more than two-thirds (69 percent) used the original framework, thus reversing the proportional distribution in the whole corpus. Notably, eight out of nine of these texts that referenced Palimpsests and used the original scope of the concept were published after 2012 when the expanded definition had already established majority in game studies scholarship. These findings suggest that although scholars are to a certain extent aware of Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation as the origin of paratextuality, they most likely rely on Consalvo’s text or only on superficial reading of Genette’s monograph.

The Future of the Paratextual Framework

Already in 1987, Genette has envisioned that the concept of paratext could be applied to other cultural fields:

[…] examples are the title in music and in the plastic arts, the signature in painting, the credits or the trailer in film, and all the opportunities for authorial commentary presented by catalogues of exhibitions, prefaces of musical scores […], record jackets, and other peritextual or epitextual supports. (Genette, 1997b, p. 407 [1987])

The field of game studies has adopted paratextuality relatively quickly, with the first notable case in 1997, and since 2012 it has become a commonly used concept. A large portion of this research, however, uses a significantly expanded version of the concept, which alters its original analytical value. In this respect, paratextuality was appropriated without full consideration of its theoretical foundations as one of the five types of transtextuality; a similar situation has been noted by Georg Stanitzek (2005 [2004]) in film studies. Taken out of the original context, scholars have reversed Genette’s intention of creating a more detailed analytical toolkit compared to Kristeva’s (1969) version of intertextuality. By broadening the scope of paratextuality to include all-game related phenomena regardless of their origin and cultural status and thus effectively conflating paratextuality with metatextuality and hypertextuality, many scholars seem to disregard Genette’s warnings about the fetishization of paratext: “Inasmuch as the paratext is a transitional zone between text and beyond-text, one must resist the temptation to enlarge this zone by whittling away in both directions. […] we will be wary of rashly proclaiming that ’all is paratext.’” (Genette, 1997b, p. 407 [1987])

While the original definition is not without its flaws and some critical conceptual legwork is necessary to enable a transition of the term grounded in literary publishing to analog and digital game industries, the expanded framework goes beyond adapting paratextuality to a new context and instead recreates the term cultural epiphenomena (Heath, 1976; Klinger, 1989) under a different name. Still, the proponents of the expanded definition have raised many valid points, such as criticizing the subordination of paratextual elements (Brookey & Gray, 2017; Consalvo, 2007, 2017; Gray, 2010; S. E. Jones, 2008; see also Lunenfeld, 1999; Rockenberger, 2014; W. Wolf, 2006) or the rigid spatial binary of peritext and epitext (Dunne, 2016; S. E. Jones, 2008; see also Lunenfeld, 1999; McCracken, 2012; Stewart, 2010; W. Wolf, 2006). These contributions are relevant for all three versions of paratextuality and have also been developed by authors working within the original and reduced frameworks. In fact, new concepts grounded in the original definition can offer tools for analyzing cultural practices that go beyond what Genette saw as the supportive role of paratextuality in ensuring the authorial intent of a text. For example, John Thornton Caldwell’s (2013, 2014) concept of the para-industry (not to be mistaken for Consalvo’s paratextual industries) addresses the fact that paratextual elements do not only refer to cultural artifacts but also represent the industries that create these artifacts (and paratextual elements). In this sense, credits or making-ofs do not only represent the origins of a text but also show how the industry perceives itself and how it wants to be perceived, for example, in terms of which type of labor or craft is highlighted above others.

I have argued elsewhere (Švelch, 2016, 2017b) that any text that exists in the socio-historical reality can be considered inherently paratextual. In other words, just the material presence of a cultural artifact even in a digital form establishes its paratextual quality if one follows Genette’s original definition. Thus, a text as an object is, in a sense, always paratextual, as it could not be otherwise approached by audiences. This means that applying “paratext” as a label for certain types and forms of texts can be misleading or, on the other hand, redundant. Such use of terminology implies that some texts are paratextual, while others are not, which goes against the original definition of paratextuality and imposes a hierarchical view on texts and their seemingly supportive elements, which has been criticized across all three frameworks (e.g. Brookey & Gray, 2017; Consalvo, 2007, 2017; Lunenfeld, 1999; Švelch, 2017a; W. Wolf, 2006). “Paratext” when used as a label for concrete phenomena might lead to oversimplification of any cultural industry (or culture) by suggesting a clear hierarchy between cultural artifacts and even among the specific types of transtextuality. Instead, I have proposed to refocus paratextual analysis on specific sources of paratextuality as “links between a text and the surrounding socio-historical reality” (Švelch, 2017b, p. 143). To do so, I suggest to reject term paratext in favor of paratextuality in order to minimize the temptation to identify cultural artifacts as “paratexts” (e.g. credits, manuals, trailers, user interface) and thus imply their perceived ancillary or subordinate position. When following this methodological suggestion, scholars would need to identify why certain aspects and elements of texts establish paratextuality (without relying on the assumption of paratextual genres and practices) as a quality of a cultural artifact that grounds it within a socio-historical reality while acknowledging that the same element can also exhibit other qualities. This proposed redefinition has support in Genette’s own writing, in which paratextuality is understood as a: “[…] canal lock between the ideal and relatively immutable identity of the text and the empirical (sociohistorical) reality of the text’s public […]” (Genette, 1997b, p. 408 [1987]) It also follows Genette’s advice, as previously quoted, to consider paratextuality “not as a classification of texts […] but rather as an aspect of textuality, […] its diverse components (intertextuality, paratextuality, etc.) not as categories of texts but rather as aspects of textuality.” (Genette, 1997a, p. 8 [1982]) This update to terminology is not meant as a direct replacement for any of the three major frameworks. Instead, it is meant as a methodological intervention that can be technically applied to all these approaches. Its main point is to avoid relying on reductive categories of texts (e.g. paratexts, metatexts) and instead recognize other co-present qualities along with paratextuality. This way, it is, for example, possible to identify the paratextual functions of trailers without implying that they are less important or subordinate just based on one of their qualities (Švelch, 2017a, 2017b).

Conclusion

In this article, I have identified three major approaches to paratextuality and provided the first quantitative overview of their influence on game studies scholarship. The frequent use of paratextuality documented in my material suggests that this analytical concept offers a productive way of exploring game cultural industries and game culture despite the competing approaches to its definition. Arguably. the two prominent versions of the framework -- the original as proposed by Genette and the expanded one, whose popularity can be attributed to Consalvo -- partially reflect the disciplinary and thematic structure of game studies.

The former is relevant to scholarship interested in game production, which can use Genette’s concept in its original form to analyze how developers and their associates communicate and frame games and games-related phenomena to players as well also among each other and to other stakeholders. This framework can also highlight tensions and inequalities between various professionals involved in game production regarding their ability to make authoritative paratextual statements (Caldwell, 2011, 2013, 2014) and, for example, to be featured in credits and have their work input recognized by both their peers and audiences. For production studies scholars, the limitation of authorship of paratextual elements, which is an integral part of the original definition, can be beneficial when distinguishing between various functionally similar phenomena (e.g. official versus player-made guides) created by different actors within game cultural industries.

The expanded definition aligns itself with research focusing on players, fans, and game cultures in general. This more inclusive and broader perspective discards the distinction between paratextuality and other types of transtextuality in favor of a more general term resembling cultural epiphenomena (Heath, 1976; Klinger, 1989). This conceptual change highlights that, for example, gaming capital can be gained by interacting with a variety of texts, both officially sanctioned and user-created. Arguably, the difference in authorship could still be relevant for investigations of fan-producer relationships (e.g. Fathallah, 2016; Herzog, 2012), but it might be methodologically difficult to distinguish between elements created by the respective parties. The expanded framework sidesteps this question and instead focuses on further decentralizing the producer-imposed hierarchies of cultural industries and their surrounding cultures.

The reduced framework, while mostly absent from game studies, could also find its use, particularly in formal analysis of games and close readings. This version of paratextuality is suitable for in-depth explorations, providing a well-defined toolkit for assessing the structural aspects of games and their potential impact on audience reception. Most notably, it deliberately strips away the somewhat contradictory notion of the factual paratext and looks at tangible elements spatially connected to a cultural artifact.

Following recent critical reflections of game studies scholarship (Martin, 2018; Quandt et al., 2015), I argue for a more rigorous use of terminology and a thorough examination of research practices. Paratextuality is only one of many concepts used in game studies but its current usage exposes the inter- and multidisciplinary nature of the field and the possible consequences of adopting of terms from other traditions. The goal of this article has not been to declare one correct definition of paratextuality, but to explicate the main differences between the widely used approaches and encourage a more conscious use of the frameworks. Articulating one’s approach to paratextuality can help to leverage the strengths of a chosen definition while acknowledging its weaknesses.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Alexandra Polownikow and Jaroslav Švelch for their valuable intellectual contribution to the theoretical discussion of paratextuality. This article has also benefitted from advice and support from my colleagues at the Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies at Tampere University, especially Dale Leorke, who helped me in obtaining several full text versions of the publications for the citation analysis. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and helpful feedback.

This work was supported by the European Regional Development Fund project “Creativity and Adaptability as Conditions of the Success of Europe in an Interrelated World” (reg. no.: CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000734).

This research was supported by the Academy of Finland project Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult, 312395).

Endnotes

[1] Seuils can be translated into English as “threshold”, hence the title Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation.

[2] "Structure and Functions of the Title in Literature" (Genette, 1988) is an excerpt from Chapter 4 of Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation about titles (Genette, 1997b, pp. 55-94 [1987]) published in the journal Critical Inquiry. Introduction to the Paratext (Genette, 1991) is a translation of the entire opening chapter of Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (Genette, 1997b, pp. 1-15 [1987]) published in the journal New Literary History.

[3] The respective forewords of these two translations (Macksey, 1997; Prince, 1997) explicated the close connection between Genette’s three texts about transtextuality (Genette, 1992, 1997a, 1997b).

[4] Several early publications from game studies have, however, used paratextuality according to its original definition (Eskelinen & Tronstad, 2003; Montfort, 2006; Perron et al., 2008; Rapp, 2007; L. N. Taylor, 2007).

[5] There is a relatively large body of research focusing on games as paratextual elements coming usually from the field of screen studies (e.g. Booth, 2015; Brookey, 2010; Chircop, 2016; Freeman, 2019; Geraghty, 2019; Gray, 2010; Janes, 2019; B. Jones, 2014; Mittell, 2015; Sullivan & Salter, 2017). These texts generally use the expanded definition and consider most transmedia elements, including games based on other intellectual properties, paratextual elements. Due to their specific focus and background in screen studies, they do not fit the other game studies texts that position games and game-related artifacts as the main phenomena. For this reason, they were excluded them from the quantitative analysis.

[6] I was unable to obtain a full text version of two academic texts whose excerpts and Google Scholar search results suggested that they discuss paratextuality in the context of games and would most likely be eligible for inclusion in the quantitative analysis (the respective references are included in the supplemented list of all analyzed texts). Considering the size of the sample, two publications cannot significantly influence the results.

References

Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aarseth, E. J. (2001). Computer Game Studies, Year One. Game Studies, 1(1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/editorial.html

Arsenault, D. (2017). Super Power, Spoony Bards, and Silverware: The Super Nintendo Entertainment System. MIT Press.

Åström, F. (2014). The Context of Paratext: A Bibliometric Study of the Citation Contexts of Gérard Genette’s Texts. In N. Desrochers & D. Apollon (Eds.), Examining Paratextual Theory and its Applications in Digital Culture (pp. 1-23). IGI Global.

Backe, H.-J. (2017). Between “Games as Media” and “Interactive Games.” Game Studies, 17(2). http://gamestudies.org/1702/articles/review_backe

Barthes, R. (1987). The Death of the Author. In S. Heath (Trans.), Image, Music, Text (pp. 142-148). Fontana Press.

Booth, P. (2015). Game play: Paratextuality in contemporary board games. Bloomsbury Academic.

Bredehoft, T. A. (2014). The visible text: Textual production and reproduction from Beowulf to Maus (First Edition). Oxford University Press.

Brookey, R. A. (2010). Hollywood gamers: Digital convergence in the film and video game industries. Indiana University Press.

Brookey, R. A., & Gray, J. (2017). “Not merely para”: Continuing steps in paratextual research. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(2), 101-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1312472

Caldwell, J. T. (2011). Corporate and Worker Ephemera: The Industrial Promotional Surround, Paratexts and Worker Blowback. In P. Grainge (Ed.), Ephemeral media: Transitory screen culture from television to YouTube (pp. 175-194). Palgrave Macmillan.

Caldwell, J. T. (2013). Para-Industry: Researching Hollywood’s Blackwaters. Cinema Journal, 52(3), 157-165.

Caldwell, J. T. (2014). Para-Industry, Shadow Academy. Cultural Studies, 28(4), 720-740. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2014.888922

Chircop, D. (2016). An Experiential Comparative Tool for Board Games. Replay. The Polish Journal of Game Studies, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.18778/2391-8551.03.01

Consalvo, M. (2007). Cheating: Gaining advantage in videogames. MIT Press.

Consalvo, M. (2009). There is No Magic Circle. Games and Culture, 4(4), 408-417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009343575

Consalvo, M. (2017). When paratexts become texts: De-centering the game-as-text. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(2), 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1304648

Consalvo, M. (2019). Clash Royale: Gaming Capital. In M. T. Payne & N. B. Huntemann (Eds.), How to Play Video Games (pp. 185-192). New York University Press.

deWinter, J., & Moeller, R. M. (2014). Playing the Field: Technical Communication for Technical Games. In J. deWinter & R. M. Moeller (Eds.), Computer games and technical communication: Critical methods & applications at the intersection (pp. 1-13). Ashgate Publishing.

Dunne, D. (2016). Paratext: The In-Between of Structure and Play. In C. Duret & C.-M. Pons (Eds.), Contemporary Research on Intertextuality in Video Games (pp. 274-296). IGI Global.

Egliston, B. (2019). Watch to win? E-sport, broadcast expertise and technicity in Dota 2. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856519851180

Eskelinen, M., & Tronstad, R. (2003). Video Games and Configurative Performances. In M. J. P. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The video game theory reader (pp. 195-220). Routledge.

Eyman, D. (2008). Computer Gaming and Technical Communication: An Ecological Framework. Technical Communication, 55(3), 242-250.

Fathallah, J. (2016). Statements and silence: Fanfic paratexts for ASOIAF/Game of Thrones. Continuum, 30(1), 75-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2015.1099150

Freeman, M. (2019). The World of The Walking Dead. Routledge.

Genette, G. (1979). Introduction à l’architexte. Éditions du Seuil.

Genette, G. (1982). Palimpsestes: La littérature au second degré. Éditions du Seuil.

Genette, G. (1987). Seuils. Éditions du Seuil.

Genette, G. (1988). Structure and Functions of the Title in Literature (B. Crampé, Trans.). Critical Inquiry, 14(4), 692-720.

Genette, G. (1991). Introduction to the Paratext (M. Maclean, Trans.). New Literary History, 22(2), 261-272. https://doi.org/10.2307/469037

Genette, G. (1992). The Architext: An Introduction (J. A. Lewin, Trans.). University of California Press.

Genette, G. (1994). L'Oeuvre de l’art: Immanence et transcendance. Éditions du Seuil.

Genette, G. (1997a). Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (C. Newman & C. Doubinsky, Trans.). University of Nebraska Press.

Genette, G. (1997b). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (J. A. Lewin, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Genette, G. (1997c). The Work of Art: Immanence and Transcendence (G. M. Goshgarian, Trans.). Cornell University Press.

Geraghty, L. (2019). In a “Justice” League of Their Own: Transmedia Storytelling and Paratextual Reinvention in LEGO’s DC Super Heroes. In R. C. Hains & S. R. Mazzarella (Eds.), Cultural Studies of LEGO: More Than Just Bricks (pp. 23-46). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32664-7_2

Gray, J. (2010). Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York University Press.

Guins, R. (2014). Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. MIT Press.

Heath, S. (1976). Screen Images, Film Memory. Edinburgh Magazine, 1, 33-42.

Herzog, A. E. (2012). “But this is my story and this is how I wanted to write it”: Author’s notes as a fannish claim to power in fan fiction writing. Transformative Works and Cultures, 11. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2012.0406

Hesford, D. (2013). ‘Action… Suspense… Emotion!’: The Trailer as Cinematic Performance. Frames Cinema Journal, 2013(3).

Janes, S. (2019). Alternate Reality Games: Promotion and Participatory Culture. Routledge.

Jansen, L. (Ed.). (2014). The Roman paratext: Frame, texts, readers. Cambridge University Press.

Jara, D. (2013). A Closer Look at the (Rule-) Books: Framings and Paratexts in Tabletop Role-playing Games. International Journal of Role-Playing, 4.

Johnston, K. M. (2013). Introduction: Still Coming Soon? Studying Promotional Materials. Frames Cinema Journal, 2013(3).

Johnston, K. M., Vollans, E., & Greene, F. L. (2016). Watching the trailer: Researching the film trailer audience. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 13(2), 56-85.

Jones, B. (2014). Unusual Geography: Discworld Board Games and Paratextual L-Space. Intensities: Journal of Cult Media, 7, 55-73.

Jones, S. E. (2008). The Meaning of Video Games: Gaming and Textual Strategies. Routledge.

Juul, J. (2010). A casual revolution: Reinventing video games and their players. MIT Press.

Klinger, B. (1989). Digressions at the Cinema: Reception and Mass Culture. Cinema Journal, 28(4), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.2307/1225392

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed). Sage.

Kristeva, J. (1969). Sēmeiōtikē: Recherches pour une sémanalyse. Éditions du Seuil.

Lunenfeld, P. (1999). Unfinished Business. In P. Lunenfeld (Ed.), The digital dialectic: New essays on new media (pp. 6-22). MIT Press.

Macksey, R. (1997). Foreword: Pausing on the Threshold. In J. A. Lewin (Trans.), Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (pp. xi-xxi). Cambridge University Press.

Martin, P. (2018). The Intellectual Structure of Game Research. Game Studies, 18(1). http://gamestudies.org/1801/articles/paul_martin

Mason, J. (2013). Video Games as Technical Communication Ecology. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(3), 219-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.760062

Mäyrä, F. (2009). Getting into the Game: Doing Multidisciplinary Game Studies. In B. Perron & M. J. P. Wolf (Eds.), The video game theory reader 2 (pp. 311-329). Routledge.

McCracken, E. (2012). Expanding Genette’s Epitext/Peritext Model for Transitional Electronic Literature: Centrifugal and Centripetal Vectors on Kindles and iPads. Narrative, 21(1), 104-123.

Mittell, J. (2015). Complex TV: The poetics of contemporary television storytelling. New York University Press.

Montfort, N. (2006). Combat in Context. Game Studies, 6(1). http://gamestudies.org/0601/articles/montfort

Montfort, N., & Bogost, I. (2009). Racing the beam: The Atari Video computer system. MIT Press.

Myers, D. (2010). Play Redux: The Form of Computer Games. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv65swkk

Nooney, L. (2014). Easter Eggs. In M.-L. Ryan, L. Emerson, & B. J. Robertson (Eds.), The Johns Hopkins guide to digital media (pp. 165-166). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Perron, B., Arsenault, D., Picard, M., & Therrien, C. (2008). Methodological questions in ‘interactive film studies.’ New Review of Film and Television Studies, 6(3), 233-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400300802418552

Prince, G. (1997). Foreword. In C. Newman & C. Doubinsky (Trans.), Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (pp. ix-xi). University of Nebraska Press.

Quandt, T., Looy, J. V., Vogelgesang, J., Elson, M., Ivory, J. D., Consalvo, M., & Mäyrä, F. (2015). Digital Games Research: A Survey Study on an Emerging Field and Its Prevalent Debates. Journal of Communication, 65(6), 975-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12182

Rapp, B. (2007). Self-Reflexivity in Computer Games: Analyses of Selected Examples. In W. Nöth & N. Bishara (Eds.), Self-Reference in the Media (pp. 253-265). Mouton de Gruyter.

Rockenberger, A. (2014). Video Game Framings. In N. Desrochers & D. Apollon (Eds.), Examining Paratextual Theory and its Applications in Digital Culture (pp. 252-286). IGI Global.

Sicart, M. (2011). Against Procedurality. Game Studies, 11(3). http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap

Smith, H., & Wilson, L. (Eds.). (2011). Renaissance paratexts. Cambridge University Press.

Spilker, H. S., Ask, K., & Hansen, M. (2020). The new practices and infrastructures of participation: How the popularity of Twitch.tv challenges old and new ideas about television viewing. Information, Communication & Society, 23(4), 605-620. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1529193

Stanitzek, G. (2005). Texts and Paratexts in Media. Critical Inquiry, 32(1), 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1086/498002

Stewart, G. (2010). The Paratexts of Inanimate Alice: Thresholds, Genre Expectations and Status. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 16(1), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856509347709

Sullivan, A., & Salter, A. (2017). A Taxonomy of Narrative-centric Board and Card Games. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 23:1-23:10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3102071.3102100

Švelch, J. (2016). “Footage Not Representative”: Redefining Paratextuality for the Analysis of Official Communication in the Video Game Industry. In C. Duret & C.-M. Pons (Eds.), Contemporary Research on Intertextuality in Video Games (pp. 297-315). IGI Global.

Švelch, J. (2017a). Exploring the Myth of the Representative Video Game Trailer. Kinephanos: Revue d’études Des Médias et de Culture Populaire / Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture, 7(1), 7-36.

Švelch, J. (2017b). Paratexts to Non-Linear Texts: Paratextuality in Video Game Culture [Doctoral thesis, Univerzita Karlova, Fakulta sociálních věd, Institut komunikačních studií a žurnalistiky. Katedra mediálních studií]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319932075_Paratexts_to_Non-Linear_Media_Texts_Paratextuality_in_Video_Game_Culture

Taylor, L. N. (2007). Networking Power: Videogame Structure from Concept Art. In A. Clarke & G. Mitchell (Eds.), Videogames and Art (pp. 226-237). Intellect Books.

Taylor, T. L. (2009). The Assemblage of Play. Games and Culture, 4(4), 331-339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009343576

Vollans, E. (2015). So just what is a trailer, anyway? Arts and the Market, 5(2), 112-125. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAM-07-2014-0026

Vollans, E. (2017). The most Cinematic Game yet. Kinephanos: Revue d’études Des Médias et de Culture Populaire / Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture, 7(1), 106-130.

Whalen, Z. (2012). Channel F for Forgotten: The Fairchild Video Entertainment System. In M. J. P. Wolf (Ed.), Before the crash: Early video game history (pp. 60-80). Wayne State University Press.

Wolf, W. (2006). Introduction: Frames, Framings, and Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media. In W. Bernhart & W. Wolf (Eds.), Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media (pp. 1-40). Rodopi.

Wolf, W., & Bernhart, W. (Eds.). (2006). Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media. Rodopi.

Ludography

Atari. (1979). Adventure [Atari 2600]. Sunnyvale, California: Atari.

Appendix 1

Publications Included in the Corpus

Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aarseth, E. J. (2004). Genre Trouble: Narrativism and the Art of Simulation. In N. Wardrip-Fruin & P. Harrigan (Eds.), First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game (pp. 45-55). MIT Press.

Abrams, S. S., & Gerber, H. R. (2014). Bridging Literacies: An Introduction. In S. S. Abrams & H. R. Gerber (Eds.), Bridging literacies with videogames (pp. 1-7). Sense Publishers.

Adams, M. B., & Rambukkana, N. (2018). “Why do I have to make a choice? Maybe the three of us could, uh...”: Non-Monogamy in Videogame Narratives. Game Studies, 18(2). http://gamestudies.org/1802/articles/adams_rambukkana

Albarrán-Torres, C., & Apperley, T. (2019 [2018]). Poker avatars: Affective investment and everyday gambling platforms. Media International Australia, 172(1), 103-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X18805088

Anderson, B. R., & Smith, A. M. (2019). Understanding user needs in videogame moment retrieval. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3337722.3337728

Anderson, S. L. (2019). The interactive museum: Video games as history lessons through lore and affective design. E-Learning and Digital Media, 16(3), 177-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957

Apperley, Thomas. (2017). Digital Gaming, Social Inclusion, and the Right to Play: A Case Study of a Venezuelan Cybercafé. In L. Hjorth, H. A. Horst, A. Galloway, & G. Bell (Eds.), The Routledge companion to digital ethnography (pp. 235-243). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Apperley, Thomas. (2018). Counterfactual Communities: Strategy Games, Paratexts and the Player’s Experience of History. Open Library of Humanities, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.286

Apperley, Thomas, & Beavis, C. (2011). Literacy into action: Digital games as action and text in the English and literacy classroom. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 6(2), 130-143.

Apperley, Thomas, & Parikka, J. (2018 [2015]). Platform Studies’ Epistemic Threshold. Games and Culture, 13(4), 349-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015616509

Apperley, Thomas, & Walsh, C. (2012). What digital games and literacy have in common: A heuristic for understanding pupils’ gaming literacy. Literacy, 46(3), 115-122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4369.2012.00668.x

Apperley, Tom, & Beavis, C. (2013). A Model for Critical Games Literacy. E-Learning and Digital Media, 10(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2013.10.1.1

Arsenault, D. (2017). Super Power, Spoony Bards, and Silverware: The Super Nintendo Entertainment System. MIT Press.

Arsenault, D., Coté, P.-M., Larochelle, A., & Lebel, S. (2013). Graphical technologies, innovation and aesthetics in the video game industry: A case study of the shift from 2D to 3D graphics in the 1990s. G|A|M|E, the Italian Journal of Game Studies, 1(2). https://www.gamejournal.it/graphical-technologies-innovation-and-aesthetics-in-the-video-game-industry-a-case-study-of-the-shift-from-2d-to-3d-graphics-in-the-1990s/

Ashton, D., & Newman, J. (2012). “Tips and tricks to take your game to the next level”: Expertise and Identity in FPS Games. In G. R. Voorhees, J. Call, & K. Whitlock (Eds.), Guns, grenades, and grunts: First-person shooter games (pp. 225-248). Continuum.

Aycock, J., & Finn, P. (2019). Uncivil Engineering: A Textual Divide in Game Studies. Game Studies, 19(3). http://gamestudies.org/1903/articles/aycockfinn

Backe, H.-J. (2018). A Redneck Head on a Nazi Body. Subversive Ludo-Narrative Strategies in Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus. Arts, 7(4), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040076

Beale, M., McKittrick, M., & Richards, D. (2016 [2015]). “Good” Grief: Subversion, Praxis, and the Unmasked Ethics of Griefing Guides. Technical Communication Quarterly, 25(3), 191-201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2016.1185160

Beavis, C., Apperley, T., Bradford, C., O’Mara, J., & Walsh, C. (2009). Literacy in the digital age: Learning from computer games. English in Education, 43(2), 162-175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-8845.2009.01035.x

Beavis, C., Walsh, C., Bradford, C., O’Mara, J., Apperley, T., & Gutierrez, A. (2015). “Turning around” to the affordances of digital games: English curriculum and students’ lifeworlds. English in Australia, 50(2), 30-40.

Bergstrom, K., Jenson, J., Flynn-Jones, E., & Hebert, C. (2018). Videogame Walkthroughs in Educational Settings: Challenges, Successes, and Suggestions for Future Use. Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 1875-1884.

Bjørkelo, K. A. (2019). “It Feels Real to Me”: Transgressive Realism in This War of Mine. In K. Jørgensen & F. Karlsen (Eds.), Transgression in games and play (pp. 169-185). The MIT Press.

Blom, J. (2018). Overwatch as a Shared Universe: Game Worlds in a Transmedial Franchise. Proceedings of DiGRA 2018. DiGRA 2018, Turin.

Bohunicky, K. M. (2014). Ecocomposition: Writing ecologies in digital games. Green Letters, 18(3), 221-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/14688417.2014.964283

Bohunicky, K. M., & Youngblood, J. (2019). The Pro Strats of Healsluts: Overwatch, Sexuality, and Perverting the Mechanics of Play. WiderScreen, 1-2.

Bourgonjon, J. (2014). The Meaning and Relevance of Video Game Literacy. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 16(5). https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2510

Burk, D. L. (2010). Copyright and Paratext in Computer Gaming. In C. Wankel & S. Malleck (Eds.), Emerging Ethical Issues of Life in Virtual Worlds (pp. 33-53). IAP.

Burke, A. (2014). Teaching with Club Penguin: Re-creating Children’s School Literacy through Paratexts in the Classroom. In H. R. Gerber & S. S. Abrams (Eds.), Bridging literacies with videogames (pp. 67-88). Sense Publishers.

Burwell, C. (2017). Game Changers: Making New Meanings and New Media with Video Games. English Journal, 106(6), 41-47.

Burwell, C., & Miller, T. (2016). Let’s Play: Exploring literacy practices in an emerging videogame paratext. E-Learning and Digital Media, 13(3-4), 109-125. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753016677858

Carter, M. (2015a). The first week of the zombie apocalypse: The influences of game temporality. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 7(1), 59-75. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.7.1.59_1

Carter, M. (2015b [2014]). Emitexts and Paratexts: Propaganda in EVE Online. Games and Culture, 10(4), 311-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412014558089

Carter, M. (2020 [2018]). Valuing Play in Survivor: A Constructionist Approach to Multiplayer Games. Games and Culture, 15(4), 434-452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412018804327

Carter, M., Bergstrom, K., Webber, N., & Milik, O. (2016). EVE is Real: How conceptions of the “real” affect and reflect an online game community. Well Played, 5(2), 5-33.

Carter, M., Gibbs, M., & Arnold, M. (2015). The Demarcation Problem in Multiplayer Games: Boundary-Work in EVE Online’s eSport. Game Studies, 15(1). http://gamestudies.org/1501/articles/carter

Carter, M., Gibbs, M., & Harrop, M. (2012). Metagames, Paragames and Orthogames: A New Vocabulary. FDG ’12: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1145/2282338.2282346

Chik, A. (2012). Digital Gameplay for Autonomous Foreign Language Learning: Gamers’ and Language Teachers’ Perspectives. In H. Reinders (Ed.), Digital Games in Language Learning and Teaching (pp. 95-114). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137005267_6

Church, J., & Klein, M. (2013). Assassin’s Creed III and the Aesthetics of Disappointment. Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies. DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies, Atlanta.

Comerford, C. (2018). Participatory toolboxes: Franchise fan wikis as tools of textual production. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 15(2), 285-296.

Consalvo, M. (2007). Cheating: Gaining advantage in videogames. MIT Press.

Consalvo, M. (2017). When paratexts become texts: De-centering the game-as-text. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(2), 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1304648

Consalvo, M. (2019). Clash Royale: Gaming Capital. In M. T. Payne & N. B. Huntemann (Eds.), How to Play Video Games (pp. 185-192). New York University Press.

Consalvo, M. (2009). Hardcore Casual: Game Culture Return(s) to Ravenhearst. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games, 50-54. https://doi.org/10.1145/1536513.1536531

Conway, S. (2010a). A circular wall? Reformulating the fourth wall for videogames. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 2(2), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.2.2.145_1

Conway, S. (2010b). Hyper-Ludicity, Contra-Ludicity, and the Digital Game. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 4(2), 135-147.

Cooke, L., & Hubbell, G. S. (2015). Working Out Memory with a Medal of Honor Complex. Game Studies, 15(2). http://gamestudies.org/1502/articles/cookehubbell

Crawford, G. (2012). Video gamers. Routledge.

Davis, D., & Marone, V. (2016). Learning in Discussion Forums: An Analysis of Knowledge Construction in a Gaming Affinity Space. International Journal of Game-Based Learning (IJGBL), 6(3), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGBL.2016070101

de Castell, S., & Jenson, J. (2018). “We should play more games!” Learning with narrative videogames. In D. M. Ciussi (Ed.), ECGBL 2018 12th European Conference on Game-Based Learning (pp. 45-53). Academic Conferences and publishing limited.

De Grove, F., & Van Looy, J. (2014). Walkthrough. In M.-L. Ryan, L. Emerson, & B. J. Robertson (Eds.), The Johns Hopkins guide to digital media (p. 520). Johns Hopkins University Press.

de Wildt, L. (2019). “Everything is true, nothing is permitted”: Utopia, Religion and Conspiracy in Assassin’s Creed. In B. Beil, G. S. Freyermuth, & H. C. Schmidt (Eds.), Playing Utopia: Futures in Digital Games (pp. 149-186). transcript Verlag.

deWinter, J. (2015). Shigeru Miyamoto--;Super Mario Bros., Donkey Kong, The Legend of Zelda. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/shigeru-miyamoto-9781628923865/

Dor, S. (2014). A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay from Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement. History of Games International Conference Proceedings, 58-73.

Dunne, D. (2016). Paratext: The In-Between of Structure and Play. In C. Duret & C.-M. Pons (Eds.), Contemporary Research on Intertextuality in Video Games (pp. 274-296). IGI Global.

Dunne, Daniel J. (2016). The Scholar’s Ludo-Narrative Game and Multimodal Graphic Novel: A Comparison of Fringe Scholarship. In Creative Technologies for Multidisciplinary Applications (pp. 182-207). https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/the-scholars-ludo-narrative-game-and-multimodal-graphic-novel/148569

Dunne, Daniel Joseph. (2014). Brechtian Alienation in Videogames. Press Start, 1(1), 79-99.

Ecenbarger, C. (2016). Comic Books, Video Games, and Transmedia Storytelling: A Case Study of The Walking Dead. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS), 8(2), 34-42. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGCMS.2016040103

Egliston, B. (2016a). Playing Across Media: Exploring Transtextuality in Competitive Games and eSports. Well Played, 5(2), 34-62.

Egliston, B. (2016b). Big playerbase, big data: On data analytics methodologies and their applicability to studying multiplayer games and culture. First Monday, 21(7). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v21i7.6718

Egliston, B. (2017). Building Skill in Videogames: A Play of Bodies, Controllers and Game-Guides. M/C Journal, 20(2). http://www.journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/1218

Egliston, B. (2019a). Quantified Play: Self-Tracking in Videogames. Games and Culture, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019845983

Egliston, B. (2019b). Watch to win? E-sport, broadcast expertise and technicity in Dota 2. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856519851180

Eilers, F. A. (2014). SimCity and the Creative Class: Place, Urban Planning and the Pursuit of Happiness. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 1(3). http://todigra.org/index.php/todigra/article/view/31

Ensslin, A. (2011a). Avatar Needs and the Remediation of Architecture in Second LifeTM. In A. Ensslin & E. Muse (Eds.), Creating second lives: Community, identity and spatiality as constructions of the virtual (pp. 169-189). Routledge.

Ensslin, A. (2011b). The Language of Gaming. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ensslin, A., & Finnegan, J. (2019). Bad Language and Bro-up Cooperation in Co-sit Gaming. In A. Ensslin & I. Balteiro (Eds.), Approaches to videogame discourse: Lexis, interaction, textuality. Bloomsbury Academic.

Ensslin, A., & Muse, E. (Eds.). (2011). Creating second lives: Community, identity and spatiality as constructions of the virtual. Routledge.

Eskelinen, M. (2012). Cybertext poetics: The critical landscape of new media literary theory. Continuum.

Eskelinen, M., & Tronstad, R. (2003). Video Games and Configurative Performances. In M. J. P. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The video game theory reader (pp. 195-220). Routledge.

Esqueda, M. D., & Andrade Stupiello, É. N. de. (2018). Teaching Video Game Translation: First Steps, Systems and Hands-on Experience. Belo Horizonte, 11(1), 103-120.

Evans, E. (2016 [2015]). The economics of free: Freemium games, branding and the impatience economy. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 22(6), 563-580. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514567052

Fassone, R. (2017). Cammelli and Attack of the Mutant Camels: A Variantology of Italian Video Games of the 1980s. Well Played, 6(2), 55-71.

Fernández-Vara, C. (2014). Introduction to Game Analysis. Routledge.

Ferreira, E. (2019). E.T. Phone Home, or from Pit to Surface: Intersections Between Archaeology and Media Archaeology. In N. Zagalo, A. I. Veloso, L. Costa, & Ó. Mealha (Eds.), Videogame Sciences and Arts (pp. 261-275). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37983-4_20